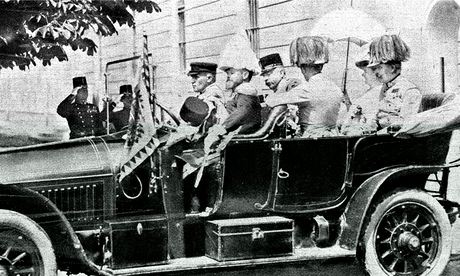

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his pregnant wife Sophie moments before they were assassinated in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Photograph: Popperfoto

"It is not to be supposed," wrote a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian analysing the significance of the assassination 100 years ago on Saturday, "that the death of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand will have any immediate or salient effect on the politics of Europe."

Thirty-seven days later, Britain declared war on Germany and Europe was plunged into a worldwide conflict in which more than 16 million people died in four years.

But it is hardly surprising that the Guardian did not predict the unimaginable horror to come. The newspaper's editorial of 29 June 1914, the day after the assassination, dwelt on the archduke's personality and on the narrow implications it might have for the internal politics of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

"What its motives may have been we do not know, nor do they greatly matter," it advised its readers. "It is a difficult and at present an ungracious task to speculate on what influence the crime of yesterday may have on Austrian politics."

The archduke, the editorial noted, was "a great gardener", adding that "in England, under other conditions of life, he would have been an ideal country squire". Franz Ferdinand was described as "a simple and amiable man, but very passionate and, in anger, uncalculable".

The Manchester Guardian, then edited by the legendary CP Scott, was far from alone in playing down the significance of the death of the archduke, shot by the young radical Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip, in Sarajevo. The Sleepwalkers, historian Christopher Clark's seminal work on how Europe went to war in 1914, reflects the mixture of complacency and rhetoric Europe indulged in.

Gavrilo Princip, the Bosnian-Serb nationalist who assassinated archduke. Photograph: Charlie Riedel/AP

Gavrilo Princip, the Bosnian-Serb nationalist who assassinated archduke. Photograph: Charlie Riedel/AP But the Guardian did devote the bulk of its main news page, illustrated by a small map and family tree of the Austrian royal house, to the shooting.

Reports from correspondents of the news agency Reuters in Sarajevo and Vienna detailed the circumstances surrounding the assassination and described an earlier attempt shortly before Princip fired the shots that killed the archduke and his wife.

The assassins were "almost lynched by the infuriated crowds … many people wept", Reuters reported.

The next day, 30 June 1914, a Guardian headline read "World's Sympathy with Aged Emperor". The paper noted that the archduke and his wife had recently visited London and, his uncle, emperor Franz Joseph, held the title of a British field marshal.

The article added: "Comments on the crime, all expressing friendly feelings for the Emperor, are made by all the European papers, most of them, as is natural while the shock is still fresh, attaching an over-importance to the political consequences."

Though the newspaper's first analysis â€" headlined What the Murders May Mean â€" played down the "immediate or salient" effect on European politics, it did warn of the dangers of increased hostility between Austria and Serbia. It also warned of "the more serious danger of a Russian attack" on Austria in defence of its Slavic ally.

The Guardian opposed British intervention right up to the declaration of war. "We care as little for Belgrade as Belgrade for Manchester," it told its readers on 30 July. On 1 August, CPÂ Scott argued that intervention would "violate dozens of promises made to our own people, promises to seek peace, to protect the poor, to husband the resources of the country, to promote peaceful progress".

Four days later, after Britain declared war on Germany, the Guardian said: "All controversy therefore is now at an end. Our front is united."

But, the newspaper added: "A little more knowledge, a little more time on this side, more patience, and a sounder political principle on the other side would have saved us from the greatest calamity that anyone living has known.

"It will be a war in which we risk almost everything of which we are proud, and in which we stand to gain nothing."

No comments:

Post a Comment