Every generation creates its own monsters. Folk tales tell of witches and wyrms in the woods, my TV-infused generation feared Jaws in lakes and Bloody Mary in the mirror. This generation gets its monsters from the Internet.

Slenderman is a pure product of electronic media. He appears in places we rarely frequent, these days â€" abandoned, crumbling halls, deep woods, a playground with a rickety steel jungle gyms. He is a suburban ghoul with his own history and his own methodology and, of late, he has become the object of controversy due to an attack in Wisconsin during which two girls stabbed another in order to appease Slenderman’s dark needs. It was a horrible story and it underlies how little we understand about the psychology of a generation weaned on the Internet and how images can morph from fiction to fact in the course of half a decade.

Slenderman’s origin is surprisingly clear. Unlike most urban legends, we can trace his provenance with absolute certainty. He was born on June 8, 2009, on a forum site frequented by Photoshop pranksters. He belongs to a guy in Florida named Eric Knudsen who has a young daughter and is surprised as much as anything that his demon hasn’t yet been thrown onto the slag heap of forgotten memes. An entire history, an entire corpus, has grown up around him in a way that would have been impossible a decade ago.

He is the first pure product of the Internet, a demon spawned not out of a specific place but out of bits. Here’s some of his story.

Slenderman first appeared on the SomethingAwful forums under a thread titled “Create Paranormal Images.†One user, Slidebite, said “You just know a couple of the good ones are going to eventually make it to paranormal websites and be used as genuine.†He was right. The first image of Slenderman- of a tall, out-of-focus figure, next to a tree â€" was accompanied by a bit of text that sounds like the dialogue from a badly-translated horror game.

“One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen children vanished and for what is referred to as “The Slender Manâ€. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.â€

â€" 1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.

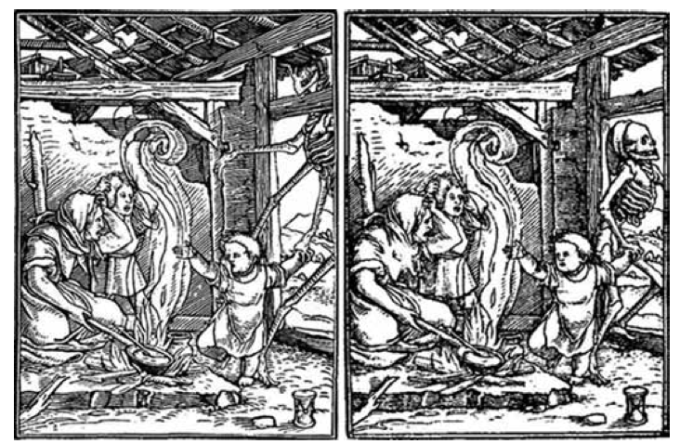

Other posters added their own interpretations of the material, creating a backstory that stretched out to 16th-century Germany and even to 5000 BC. The creator, Victor Surge, added a few more photos, while other visitors created their own. One particularly clever image is a modified woodcut. In the original, a skeleton takes a child from its parents, perhaps into death. In the modified version, the skeleton has long arms and legs and its misshapen skull is hidden by the eaves of the house.

Over the intervening months, SomethingAwful posters and fan fiction enthusiasts added to the corpus. He gained a specific definition, courtesy of a poster on Yahoo Answers in 2011, two years after the original posts:

The Slender Man is a supernatural creature that is described as appearing as a normal human being but he is described as being 8 feet tall and he has vectors or extra appendages that are described to be as sharp as swords. The creature is known to stalk humans and cause many disappearances. He is described as a shadow creature that has missing a face. The creature fits into many mythologies in legends from nations such as germany and celts which brings up the possibility that he could be real. A man named victor Surge found this legend and made his own version of it which he called slender man. The slender man is not exactly evil according to mythology but victor Surge’s version shows him as an evil creature that stalks humans to kill. In mythology he was actually trying to save you from a painful death by taking you to the under world early.

Slenderman is a product of this century. He appears and havoc follows. He murders in undescribed ways or he compels others to murder. He is a dark god in an age of digital media and he fills the empty place between the news and the unknown.

Interestingly, Slenderman was born of the previous generation’s boogeymen. From a long interview with Slenderman’s creator, Knudsen AKA Victor Surge.

: I was mostly influenced by H.P Lovecraft, Stephan King (specifically his short stories), the surreal imaginings of William S. Burroughs, and couple games of the survival horror genre; Silent Hill and Resident Evil. I feel the most direct influences were Zack Parsons’s “That Insidious Beastâ€, the Steven King short story “The Mistâ€, the SA tale regarding “The Rakeâ€, reports of so-called shadow people, Mothman, and the Mad Gasser of Mattoon. I used these to formulate asomething whose motivations can barely be comprehended and causes general unease and terror in a general population.

The key word there is terror. Slenderman does not directly kill his victims. Instead, he encourages others to in order to please him. Interestingly, the places he haunts are all but gone now. Thanks to breathless news coverage of murder and mayhem, children are rarely allowed to wander in woods alone or play in abandoned buildings. In fact, that he exists at all is a testament to the eerie pull of these places. He’s the ghost in the parking lot patrolled by bored guards and CCTV cameras. He’s the story that keeps you up at night in the center of a city full of 8 million people. He’s not Osama bin Laden or your father’s PTSD but is instead something far easier to understand. In a world that no longer harbors nameless dread, in which every monster has a name and GPS coordinates, he is a welcome refuge into the imagination.

One popular video game created around the mythos involves walking through a darkened forest surrounded by chain-link fence. All you have to do is find eight pieces of paper tacked to nearby trees. As you find the papers, the buzzing of crickets and the rustling of the photorealistic trees changes to a steady pounding. Slenderman is afoot. He doesn’t kill you. You simply disappear in a cloud of electronic snow.

Forums and video series were filled with fan fiction and content. The quality varies widely but it has grown oddly popular. One popular web series, MarbleHornets, is described as found footage of a man haunted by Slenderman. Most of the footage is mundane b-roll of woods and country roads. Then, every so often, Slenderman appears by fuzzing out the screen or pushing one of the characters into a violent coughing fit. There are no demons screaming “Gotcha.†Instead, you get an endless, nameless dread.

Wanting to find out the draw, I asked on the forums and chat rooms for input on the phenomenon. One Reddit fan, MLPTTM, wrote:

I like him because most creepypastas try to scare you with blood, gore, and if you’re lucky hyper-realistic blood. Slenderman scared me with psychological horror; making me scared of fields, trees, and sometimes nothing. He has made me as paranoid as I’ve been in my life and I love the thrill. His design is simple and terrifying because it can make him visible in a field or invisible in a forest. His humanoid figure makes him seem real like him stalking you can happen. I think the biggest thing that makes him interesting is that nobody has any full idea what happens when he gets you.

Another poster said they liked Slenderman because he was relentless:

Slender hunts you, but he doesn’t bang on your door, claw at your walls or howl at the moon. He’s just there, standing, waiting in the corner of your eyes. It’s bogus, you know it. You’re just seeing things ’cause you’re tried as shit. Or it’s Jake, pulling your leg.

Then it gets real, you have to get away. Despite your best efforts, Slender is still there. Always standing, always waiting, always watching.

Sadly, he’s also taken on a life of his own.

To understand what Slenderman has become of late all you have to do is watch a Twitter stream of mentions. In 2014, Slenderman is now Slendy, a quasi-comical, quasi-serious figure that has taken on a life of its own. The feed is full of game walkthroughs and links to creepypasta â€" essentially fan fiction â€" as well as bits of doggerel that sound like early Eminem lyrics passed through Hogwarts:

Slendy is a sort of goblin that posters use to scare themselves. Sadly, he’s also become a focal point for madness.

On May 31, two 12-year-old girls in Waukesha, Wisconsin stabbed a third girl nearly to death. The girls, who called their plot “Stabby, stab, stab†said it was intended as a sacrifice to Slenderman. Authorities are trying the pair as adults pending a mental evaluation. The tragedy here is that all the girl’s lives are damaged now â€" even potentially ruined.

The girls believed Slendy would appear to them if they killed in his name. They also believed he had threatened them and their families and could read their minds. Girls have always had fanciful flights of imagination. These claims sound much like the Salem witch hunts of the 1690s when young girls accused each other of riding with the devil. The resulting panics led to countless false confessions and over 20 executions. The same could probably happen here.

Then a few days later, around the anniversary of Slenderman’s creation, a teen in Cincinnati attacked her mother. The teen, who had a history of mental illness, was obsessed with the character. The lack of detail in this and the previous case points more towards mental illness than anything else. Slenderman, then, became the a focus for a mania that forced these girls to act out violently.

Thus far, no more reports of Slenderman-related violence have surfaced. The creators and maintainers of the mythos are adamant about their disapproval. “We are not teaching children to believe in a fictional monster, nor are we teaching them to be violent,†wrote Creepypasta moderator David Morales.

“I am deeply saddened by the tragedy in Wisconsin and my heart goes out to the families of those affected by this terrible act,†said Slenderman creator Eric Knudsen. I attempted to contact him for this story, to no avail.

Where the Slenderman mythos goes from here is anyone’s guess. He is a new villain, a new scapegoat, and a new demon. He won’t be the last of his kind but he is the first pure product of the Internet, a digital demon that haunts websites and sometimes spills over into the real world. Thankfully, no one has yet been killed in his honor. The 12-year-old Wisconsin victim is recovering and doing well.

In a statement, the girl’s parents wrote:

“Our family would like to thank everyone who has supported our daughter on her miraculous road to recovery … Our little girl has received thousands of purple hearts from numerous countries and from most continents. We simply cannot put into words how grateful we are for the prayers, packages and heartfelt messages. We are overwhelmed by the outpouring of love and support.â€

They added: “Together as a family, we continue to adjust to our ‘new normal.’ Though many days consist of medical appointments and rehabilitation, recently she and her father enjoyed a ‘daddy-daughter night at the movies’ and thoroughly enjoyed a Disney film. It also included (after much persistence) a stop for a much-deserved treat in the snack area.â€

Knudsen, for his part, stopped development of the character a few years ago. “I don’t spend a lot of active time on the Internet since I usually have a lot of real-life stuff going on,†he said.

IMAGE BY Bryce Durbin