Jesus Christ was an alien.

That may not necessarily be the first thing that comes to mind after you've seen Prometheus, director Ridley Scott's 2012 prequel to his first hit, 1979’s Alien. But these are the kind of insane, inspired, somehow totally plausible extrapolations viewers draw from Scott's movies. Scott doesn't exactly lie as a filmmaker. As a fine-arts student who got his start in the vulgar world of commercial directing and slick TV shows, he has always subverted expectations. You think you're getting a slam-bang war movie? Here's the ultimate story of bureaucratic failure (with explosions). Looking for the quintessential interstellar extraterrestrial adventure? Instead, take the most grotesque body-horror movie ever made. Scott's movies are delivery systems for ideas, but they're also Trojan horses â€" hulking, beautiful objects, meant to distract audiences while those ideas creep in, one soldier at a time, to take over your mind. It's been an effective, unlikely strategy for the British-born filmmaker. He's a three-time Academy Award nominee for Best Director â€" zero wins â€" and his 21 feature films have a lifetime box office gross of $1.25 billion. His name implies prestige, big-time moviemaking on a grand scale: Gladiator, Black Hawk Down, Blade Runner. But he's often at his best when he zooms in on the internal horrors of people's lives â€" a beleaguered king contemplating war, a scientist tortured by her pregnancy, a cop trying to protect a widow witness.

Today, the 75-year-old Scott's 22nd movie, the Cormac McCarthyâ€"penned The Counselor, arrives and it's another trick: a flashy, sleazy homage to his late brother, Tony Scott, who committed suicide last year, masquerading as a steely crime drama from staid old Ridley. (It may henceforth be known as Cameron Diaz Has Sex With a Car in This Movie.) Here, we take a look at four distinct moments of Scott flipping classic Hollywood genres right on their heads in service of his vision.

War Is Hell

The Trojan Horse: Black Hawk Down (2001)

The Other Movies: The Duellists (1977); G.I. Jane (1997); Body of Lies (2008)

The Pitch: A very modern war movie.

The Actual Product: “Only the dead know an end to war,†reads the Plato quote at the beginning of Scott’s 2001 film. The living? They have to get up and go to work every day, which is its own kind of hell.

Ridley Scott’s adaptation of Mark Bowden’s 1999 nonfiction account of the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu was released into a very different world than the one in which it was made. Hitting theaters in December '01, it was an unintentional post-9/11 movie and, in that sense, it has always been a difficult film to parse: It’s an elaborate, complex story told under a near-constant barrage of automatic-weapon fire. You're left a little confused about what exactly Scott is trying to say about war. Maybe that’s because it’s not really a war movie at all.

Black Hawk Down is actually a workplace drama. The film came out three years after Saving Private Ryan, and in terms of viscerally rendering battle onscreen, that’s its only equal. But where Saving was about the greatest generation and featured recognizable movie stars fighting against a real and obvious enemy, sacrificing their lives for something bigger, Scott takes the world’s best-trained soldiers â€" Navy SEALs, Army Rangers, Delta Force, Special Ops â€" and turns them into working stiffs, assembling a huge cast of bright young things and making them indistinguishable from one another (and that’s before they put on matching helmets and goggles).

Want that fun scene in which you find out where everyone’s from? Nope. Want to know who the “explosives guy†is, who the “wild card†is, and who the corn-fed guy from Iowa who could win the war if they only let him fight with his fists is? Wrong movie. Here we have â€" deep breath â€" Josh Hartnett, Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner (that’s half of a Trainspotting reunion!), Orlando Bloom, Eric Bana, Tom Sizemore, William Fichtner, Jeremy Piven, Hugh Dancy, Ron Eldard, Tom Hardy, Ty Burrell, Danny Hoch, Brendan Sexton III (though his part was cut down, allegedly for political-messaging reasons), Nikolaj Coster-Waldau (The Kingslayer!), and Ioan Gruffudd ... half of whom you had no idea were in this movie because there are probably three dozen speaking parts and aside from Bana, McGregor, Hartnett, Sizemore, and Sam Shepard it’s basically impossible to know who is talking and what they’re talking about.

Scott could have populated a "Young Hollywood" photo shoot with this cast, but instead he makes them look like drones. Not the military kind, but anonymous, working schmoes. They’re even wearing khakis (OK, desert camouflage, but it’s close). They all look the same, talk the same, and many of them have the same ambivalent trepidation about what they’re doing with their lives and the reasons they’re doing it.

For the first 40 minutes of this film â€" until Bloom’s Blackburn character falls from a helicopter, triggering a series of disastrous encounters between American military and Somali militia â€" this film isn’t about how modern war is hell as much as it’s about how modern work is hell.

Cafeteria lines are cut by alpha males, clerical errors are made, data entry is performed, people gripe about hours, food, and benefits, and boredom reigns. Everybody looks the same, everybody talks the same, and the fight they are there to have is treated in the same clinical way as an endless game of Scrabble. Everything is a distraction from the malaise of committing your life to your work.

Even when the fighting starts, our heroes are still working stiffs. They are constantly being vexed by institutional failures, bureaucratic nightmares, procedural hangups, and horrible bosses. Oh yeah, everybody’s got bosses, even Navy SEALs. Soldiers have to wait for permission to do everything, even save lives. And every time they look up, Big Brother (or someone higher up the chain of command) is sitting above them in the sky, watching their every move. In surveillance planes, high above the actual battle, commanding officers give faulty direction to the soldiers down below, trapping them in firefights and traffic jams, sending them down dead ends. Back at camp, decisions are made with an eye toward political fallout rather than the safety and success of the people doing the actual job. It’s like your average American workplace, just with more gunfire and burning tires.

Even the moment of glory at the end of the film, when the remaining soldiers make it, on foot, to the U.N. Safe Zone, is clouded by office politics; the safety of the soldiers is compromised because of procedural errors. Shepard’s General Garrison is reduced to a pleading middle manager:

For Scott, these conflicts and this part of the world are not solely interesting because of the quagmire they present to the American espionage and military communities; they’re compelling because they are the perfect canvas upon which to paint humans against inhumane institutions. Seven years after Black Hawk, Scott made Body of Lies. It was based on journalist David Ignatius’s novel about a CIA agent (Leonardo DiCaprio) trying to execute a dangerous operation in the Middle East, while his handler (Russell Crowe) alternatively helps him and compromises him at various turns. Scott presents Crowe’s villainous Ed Hoffman as a bloated, Bluetooth-rocking Machiavelli, ordering hits on operatives while attending his kid’s suburban Virginia soccer practice, all while DiCaprio’s Roger Ferris lives out the consequences of those corporate decisions.

You can see why this appeals to Scott; a painterly director who makes big-budget films for huge, multibillion-dollar conglomerates, he strives to make individual art in a corporate structure. No wonder one of his main themes is man vs. the modern machine of business.

Science Fiction

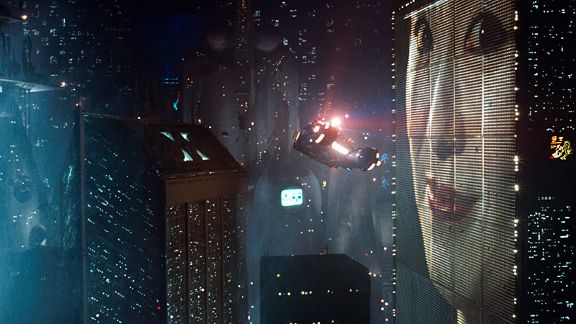

The Trojan Horse: Blade Runner (1982)

The Other Movies: Alien (1979); Prometheus (2012)

The Pitch: A sleek, futuristic action thriller.

The Actual Product: Technically, the pitch is accurate â€" Blade Runner has all the things an audience would want from a sci-fi actioner: shootouts, cyborgs gone rogue, mad scientists, flying cars, Rutger Hauer's dead-eyed Aryan heavy. But the way it's delivered relies on another kind of fiction. For his adaptation of Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Scott didn't take the Spielberg route (2002’s shimmering, hazy Minority Report) or the Paul Verhoeven route (1990’s satirical, loopy Total Recall), or even the John Woo route (2003’s straight-faced, godawful Paycheck). Scott was the first director to tackle a Dick story â€" and is still the only one to have nailed it â€" and rather than try to replicate Dick's meticulously odd, searing story, he turned to the darkness. To be more specific, the noir. Scott's third movie is a technical wonder, as advanced and influential as any sci-fi film of the last 40 years. It's one of the few movies about the future that might actually resemble the future. But it has far more in common with The Maltese Falcon â€" shadows, rain, narrative knottiness, femme fatales, wry narration (in the original version of the movie), a caustic hero â€" than with Star Wars. The archetypes are everywhere. Harrison Ford's down-on-his-luck Rick Deckard (a callback to Humphrey Bogart's Rick in Casablanca?) is a Blade Runner â€" a Secret Serviceâ€"style assassin cop tasked with killing six rogue androids called "replicants" before they do any more damage in 2019 Los Angeles. The replicants represent different visions of seedy America â€" the vicious stripper, the cold-blooded psychopath, the manic, fatherless child. Along the way, Deckard encounters a Sydney Greenstreet type, a Mary Astor type, a Peter Lorre type. They're callbacks to a past as doomed as the future.

This isn't the first time Scott has taken a science-fiction setting and contorted it into an Old Hollywood homage (with some elevated gore): His second feature, Alien, is arguably the second-most influential sci-fi movie ever; it's also secretly the most influential horror movie of all time. Scott's smart; he knows that the terrifying things, the suspense, the terror, sit in the small moments. Like this Blade Runner scene, an absurd showdown between Deckard and Daryl Hannah's Pris in an overgrown dollhouse:

Sure, there's "Superfly" Jimmy Snuka aerial combat, Hannah rocking the eye makeup of a deranged Kabuki performer, a scissor-legs chokeout, and a hand-cannon explosion happening in that scene. But it's the slow, grinding horror of the confrontation that makes it so hard to bear. Likewise the ambiguity of the story, which through the various iterations of the movie â€" few beloved movies have been recut and labeled "Director's Cut" as many times as Blade Runner â€" have become increasingly opaque about Rick's fate and true identity. He's a drunk, a loser hero, a borderline crook himself. But he's not without compass, forced into duty and seduced by an unknowable temptress. ("The report read 'Routine retirement of a replicant,'" Ricks says at one point. "That didn't make me feel any better about shooting a woman in the back.") Scott has always worked well in the dark, transposing flashes of light onto grim visions of the future â€" he began as a director of commercials, his most famous being the iconic "1984†for Apple that aired during the Super Bowl. For some, that means the hazy religious allegory of last year's Prometheus, a monster movie acting under the guise of a creation myth. For others, like Blade Runner’s many fans, the light barely shines from under the black. Life is a long, dark haul. Pack a weapon.

Swords and Sandals

The Trojan Horse: Gladiator (2000)

The Other Movies: Legend (1986); 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992); Kingdom of Heaven: Director's Cut (2005); Robin Hood (2010)

The Pitch: Russell Crowe vs. the Roman Empire.

The Actual Product: This is Scott's most successful film. It won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor; made nearly half a billion dollars; and turned Russell Crowe, albeit briefly, into the biggest movie star in the world. It took a very complicated time (ancient Rome) and presented it in an uncomplicated way: There was a hero, he was betrayed, his family was taken from him, he went through the figurative wilderness, and he returned, winning vengeance for himself and freedom for his people.

Like many of Scott’s films, it pits one competent individual (Crowe’s Maximus) against a corrupt institution (the Roman government) and a mewling villain (Joaquin Phoenix’s delightfully tweaked Commodus). And like many Scott films, the world-building is stunning. You hear every thud, stab, and dying breath in the battles, you see the doves burst out over the Coliseum and overhear every conspiratorial whisper in the Senate chamber. But, in the end, Gladiator could have been set anywhere â€" the Wild West, Arthurian times, wherever. This isn’t a film about Rome. It’s a film about morality.

“What we do in life echoes in eternity,†read the tagline. There is talk of gods, defying them, honoring them, all of that. But Scott is presenting, with his protagonist and antagonist, a very simple debate: Do you live your life in a certain way, with the understanding that there is some reward waiting for you after you die, or do you figuratively (and literally!) stab people in the back, covet your sister, and hoover up power because this life is the only life? Maximus has faith that his life does not end with death. Commodus has no such illusions. This, really, is the central struggle of Gladiator.

The moral code set up by Scott is nondenominational. While Crowe’s Maximus may die for Rome’s sins, he’s hardly a Christ figure. Scott prefers the warrior’s code to the New Testament, and you can see that in his other work. This is an artist whose fascination with religion is matched only by his deep reservations about its corrupting powers.

When Prometheus was released, Scott told Esquire, “[P]icking up a newspaper every day, how can you not despair at what's happening in the world, and how we're represented as human beings? The disappointments and corruption are dismaying at every level. And the biggest source of evil is of course religion ... Can you think of a good one? A just and kind and tolerant religion? Everyone is tearing each other apart in the name of their personal god. And the irony is, by definition, they're probably worshipping the same god.â€

This is one of Scott’s primary themes. He may be telling a story about the search for extraterrestrial life (Prometheus), or the conquering of the Holy Land (the excellent Kingdom of Heaven, which, cue Simpsons Comic Book Guy voice, you should see the director’s cut), or actual biblical tales (his next film is rumored to be Exodus, his telling of the story of Moses), but he is deeply fascinated by the toxic power that tends to follow closely on the heels of true belief. Funnily enough, I imagine only a true believer could tell stories like that. Why else would it bother him so much?

Cops and Criminals

The Trojan Horse: Thelma & Louise (1991)

The Other Movies: Someone to Watch Over Me (1987); Black Rain (1989); Hannibal (2001); Matchstick Men (2003); American Gangster (2007); The Counselor (2013)

The Pitch: Two country gals take a crazy vacation to the Grand Canyon.

The Actual Product: A feminist manifesto, a sharp-tongued buddy comedy, an existential drama, and the birth of Brad Pitt. Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon star as the titular pair of Oklahoma women in this movie about what happens when all the men you encounter are duplicitous scum. For Scott, who had spent the previous 15 years crafting moody, blackened portraits of mythology and aliens and the Yakuza, it was a kind of career relaunch. In fact, he'd been scaling back his ambitions and casting his movies in deeper shadow with each release, starting with Alien and going all the way through the intense but muddy Black Rain a decade later. Thelma & Louise lets a little sunshine in, though it's not without its own moral ambiguity. Sarandon and Davis's characters are not saints, nor even law-abiding citizens. They steal, terrorize, and gun down their assailants. They imagine a life on the road as outlaws: Bonnie and Bonnie. With a script by Callie Khouri â€" who won an Oscar and would later create ABC's Nashville â€" Thelma & Louise completely recalibrated the kinds of movies Ridley Scott was allowed to make. Strong women would appear again in G.I. Jane, the zippy, underrated Matchstick Men, and the woeful Hannibal (featuring Julianne Moore as a recast Clarice Starling). But he never quite replicated the tantalizing chemistry here. Take this scene, when Thelma and Louise are taunted by a lewd trucker and exact their revenge:

There's no remorse â€" just an exploded tanker truck and a lot of hooting and hollering. Ridley Scott movies to this point have no use for sunshine, country music, women, or laughs. Thelma & Louise has ’em all. But it's more than a gal-pal road movie. It's an antic, hyper-real frame for every crime movie that would follow, from Hannibal’s gruesome opera to American Gangster’s baroque, period criminality down to this week's cosmic cheetah-print exploitation picture, The Counselor. Scott needed to meet Thelma and Louise before he could let his freak flag fly. Just one more trick from a magician.

No comments:

Post a Comment