It began like so many creative endeavorsâ€"with a barstool discussion. “Who would be your television dad?†New York artist Amanda Tiller mused. A friend chose Cliff Huxtable, Bill Cosby’s alter ego on The Cosby Show.

Later, Tiller thought a lot about Cosby and his famously be-sweatered character: We all know Cliff, a beloved father, doctor, husband, jazz enthusiast, and Hillman College graduate. We also know Cliff’s wife, Claire, and the study habits, clothing preferences, and attitudes of their adorable children. We even know the kids’ grandparents.

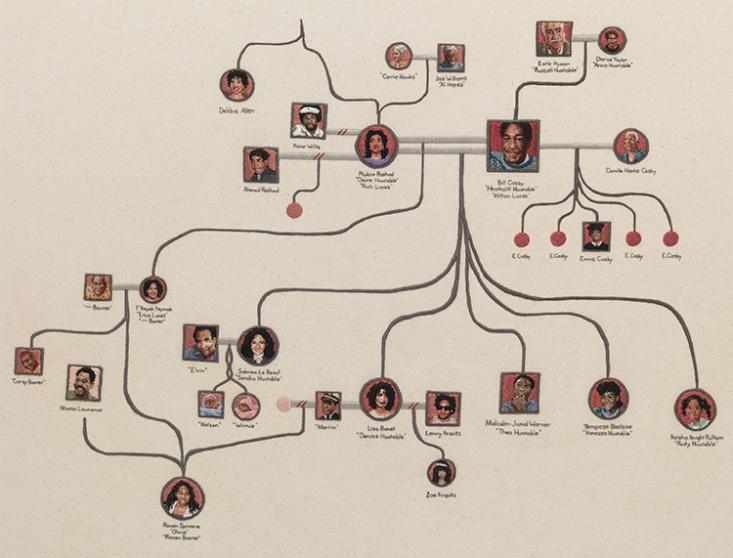

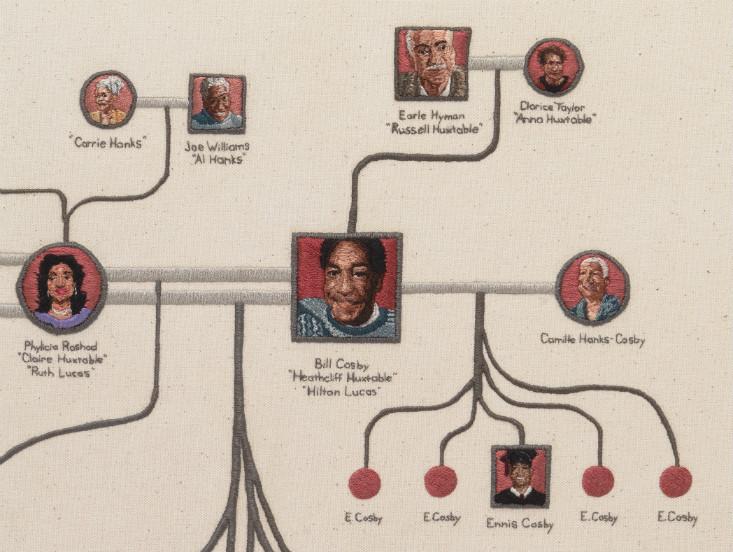

What fascinates Tiller about Cosby and other famous actors is that the fictional and real become combined in our collective unconscious. We know the stories of these faux families, and with today’s tabloid culture, real-life dramas also become entertainment. Thus she created the Genograms series: embroidered family trees like her grandmother used to make, but with actors and their fictional characters entwined together.

But Tiller isn’t an embroidery artist. She’s a memory artist. She sketched out every Cosby and Huxtable relationship she could remember. No Google, YouTube, or IMDB allowed. A total of 33 people, simply recalled.

Actresses Phylicia Rashad and Lisa Bonet were easy. But Tiller’s knowledge went deeper. The name of Cosby’s real wife, Camille. The fact they had the same number (five) and gender-order of children as on the Cosby Show (two girls, one boy, two girls), and that all of the real kids’ names began with “E.†She remembered the full name of their son, Ennis, because he had been tragically (and infamously) killed in 1997. She even remembered the six-degree type of connection between Raven-Symoné and Martin Lawrence (Raven-Symoné played Denise Huxtable’s stepdaughter as a little girl; later she played Lawrence’s daughter in College Road Trip). But other details that she couldn’t recall remain empty, such as the four children recorded vaguely as “E Cosby.â€Â

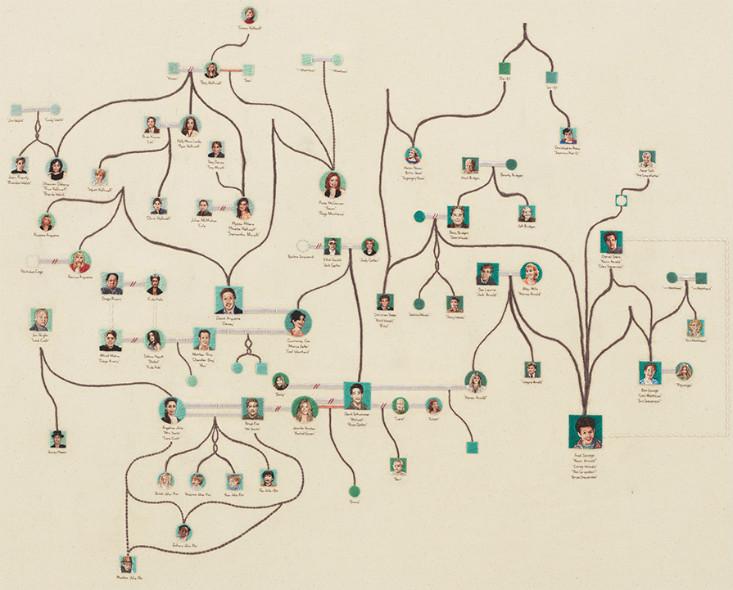

Soon after, Tiller began work on a Fred Savage genogram, based on his starring role in The Wonder Years. Now she’s moved on to a Bob Saget, which she says is huge.

Another series of Tiller’s is her movie posters, in which she describes movie plots from memory, including dialogue, costumes, and settings, then lays this text over the movie poster. “My real interest is in memory. I have a good one, but unfortunately it’s not for useful things,†she said.

In many ways, Tiller’s work is a challenge to our Internet culture. She graduated from art school in 2007 and remembers how different discussions with friends were before the now-ubiquitous smartphone. It was a recent but seemingly distant era in which she had to actually know, or horror of horrors, ask friends or strangers, the name of a song playing, a particular movie’s director, or the location of a well-hidden bar. “If we didn’t remember something, you didn’t have that ‘out’ to google it. You had to try to remember together, and think things through,†she recalls.

This emergence of fingertip Google has some worried that we’re offloading our minds into the ether, and that it might permanently get lost there. Nicholas Carr, in his book The Shallows, asserted that there is evidence that the Internetâ€"with its barrage of ads, updates, links, and pingsâ€"can rewire us neurologically, making it difficult to read and comprehend subjects on a deeper level. Tiller herself uses the Internet a lot and finds reading long articles a challenge. It seems to be a common refrain.

Others say Internet searches are really nothing new. Humans have always used outside sources for information, whether books, Post-its, or friends. It’s called transactive memory, described well by Clive Thompson in his new book, Smarter Than You Think. Couples and co-workers, for example, often split transactive memory tasks: only one person needs to know where the Ikea Allen wrench is, or remember what a client requested. So when it comes to googling information in a crowded room, what we’re doing is something we’ve always done, just with a computer network, rather than a person, as our partner. What this implies is that we’re not getting dumber, or more dependent on technology to remember things for us (if you count paper as a technology). We’re simply getting less reliant on each other for that information.

Gary Small, a psychiatrist at UCLA who researches how using the Internet influences brain activity, has found that it can promote brain activation in older adults but can also lead to a loss of social intelligence and empathy in young people. It can also make for more productive, creative learning.

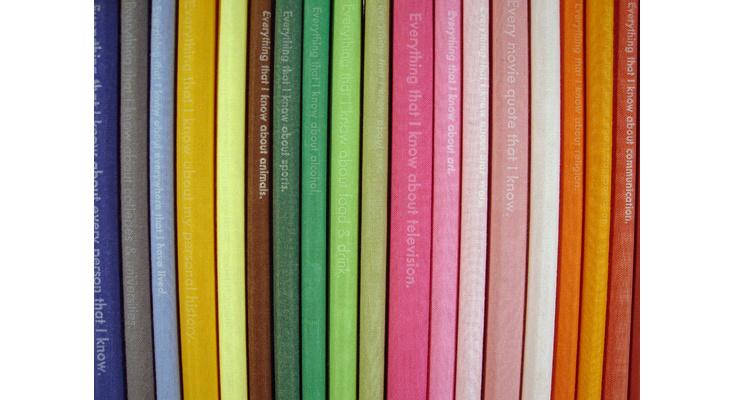

Another ongoing project of Tiller’s is Everything that I Know, in which she records every fact she can remember, in a series of color-coded books. Movie quotes fill a single tome. Facts on alcohol fill another. All 36 books, like most of her work, are handcrafted. “The pieces are purposefully analog,†she explains, “so that I have to sit and focus on them. I find that really important. I’m exploring my Internet-influenced life by not being online.â€

Heather Sparks explores art and science at Science Sparks Art. She studied molecular genetics at The Ohio State University, has a graduate degree in science journalism from New York University, and currently lives in Brooklyn.

No comments:

Post a Comment