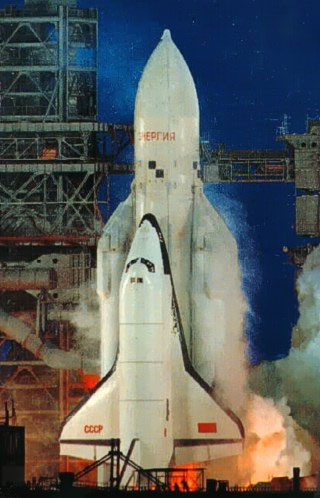

Buran being launched on its only trip into space.

But on the pad stood the Energiya rocket, fueled and ready to carry the Buran space shuttle orbiter on its maiden flight. A thin layer of ice coating both vehicles threatened to postpone the event, though no one on site wanted to see the spacecraft stay on the pad. A scrubbed launch could delay Buran’s debut until the springâ€"or even deal a death blow to the whole program. Weighing the odds, Soviet space officials decided to take their chances. At 8:00am local time, exactly on schedule, Energiya roared to life and Buran took flight.

The next morning, half a world away in the United States, American reports on the mission focused as much on Buran’s similarity to NASA’s space shuttle as on the flight itself. The Soviet design seems indebted to NASA, newspapers proclaimed, citing experts’ opinions that there were few, if any, fundamental differences between the spacecraft. This sentiment has persisted in the general public’s mind for the nearly 30 years since Buran flew.

There’s certainly truth to reports that the Soviets copied the American shuttle, but the two vehicles aren’t identical. And while imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, this wasn’t what the Soviets had in mind when they decided to build a space shuttle of their own.

The end of Apollo and the advent of the Space Shuttle

After successfully landing humans on the Moon in 1969, NASA began planning its next major program. There were a handful of options, including continued lunar exploration or the construction of an Earth orbital space station and reusable spacecraft combination. But NASA’s budget was shrinking rapidly, and after weighing the finances of the options, President Nixon made a decision. On January 5, 1972, he issued a statement saying that NASA would turn its attention to building an “entirely new type of space transportation system designed to help transform the space frontier… a space vehicle that can shuttle astronauts repeatedly from Earth to orbit and back.†NASA would build a space shuttle, even though it lacked a space station to service.

As the program took shape, NASA presented the shuttle as the vehicle that would make spaceflight routine without breaking the budget. It would also make spaceflight cost-effective, in part because the US Department of Defense would be sharing the cost. That deal meant that the DOD set the dimensions of the shuttle’s payload bay so it could carry military satellites into orbit.

The American announcement of the shuttle program didn’t immediately sound alarm bells in the Soviet Union. Having lost the race to the Moon, the nation wasn’t looking to begin another competitive program. Instead, the Soviets were focusing on the loftier goal of building a manned base on the Moon, a useful scientific endeavor that would also surpass the Americans’ six brief visits with Apollo missions. Between this lunar program, the ongoing Soyuz and Salyut programs, and the existing launch vehicle programs, there wasn’t a design bureau in the Soviet Union with enough time to work on developing a reusable shuttle. More to the point, there was simply no obvious need for such a spacecraft in the Soviets’ space program.

But plans for a lunar base hit a wall in 1974. Vasiliy Mishin, head of the TsKBEM design bureau that was once led by Sergei Korolev, was sacked and replaced by Korolev’s old rival Valentin Glushko. Glushko merged TsKBEM with his own KB Energomash organization to form a new bureau called NPO Energiya. And his first move in his new position was to halt all work on the lunar project and its associated N-1 launch vehicle so that he could consider other possible directions. He established a working group to study various reusable spacecraft, and as the lunar base fell out of favor, the idea of a shuttle moved to the foreground.

Glushko’s shuttle got a boost a year later. By 1975, the Soviet military had three years to brood over what the Americans might be up to with a reusable spacecraft as large as the one they were building. NASA even made details about its shuttle program public, so there was little guesswork needed on the Soviets’ part. Soviet military studies found that the American shuttle wouldn’t be economically viable given the parameters NASA announced, and its payload capacity seemed too high for a civilian program.

Launching up to 60 times per year with the capacity to lift nearly 25,000 kg into low-Earth orbit meant that the United States could put a lot of hardware into space each year. It seemed plausible that the Americans were planning to launch experimental laser weapons into orbitâ€"and with the shuttle’s capacity to bring 15 tons back from space, these weapons could be tested in orbit and then be brought back for modification. In the long term, this capability would let the Americans build a functioning orbital battle station.

Soviet fears seemed to be confirmed with the announcement that a shuttle launch facility would be built at the Vandenberg Air Force Base to facilitate DOD launches. And when NASA announced the shuttle’s 1,242-mile cross-range capability, the spacecraft itself started to look like a weapon that might be able to dip into the atmosphere and drop bombs. The Soviets could only conclude that the American shuttle was a military program, and responding in kind became a national priority.

The Soviet space shuttle decision

Faced with the poorly understood threat of a military space shuttle, the Soviets decided that copying the American spacecraft exactly was the best bet. The logic was simple: if the Americans were planning something that needed a vehicle that big, the Soviets ought to build one as well and be ready to match their adversary even if they didn’t know exactly what they were matching.

After a series of meetings between officials of the Ministry of General Machine Building, the Ministry of Defense, and the NPO Energiya organization, the Soviet shuttle program began on February 17, 1976. That’s when an official decree titled “On the Development of a Reusable Space System and Future Space Complexes†was issued by the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party and the Council of Ministers of the USSR. It described the new vehicle as one that would counteract military measures taken by “the likely adversary†in space; contribute to national defense, economy, and science goals; support the expansion of the military into space; and put objects into orbit and return them for servicing.

Meeting these goals would give the shuttle three mission profiles: short missions three days or less to place heavy payloads into orbit; medium duration missions lasting up to eight days during which crews could deploy and service satellites; and long duration missions, lasting up to 30 days, that would be devoted to science goals.

Superficially, the Soviet shuttle, formally called the Reusable Space System, had the same goals as the American version. But there was one crucial difference between the two programs: the Americans planned for the shuttle to take the place of all existing launch vehicles, while the Soviets’ shuttle would add to their roster of rockets. Work would continue on both the Soyuz and Salyut programs as well as the Mir space station.

Listing image by Wikimedia Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment