The rules behind the naming rights for cosmic rocks

Mary Lou Whitehorne was at a work conference in 2007 when her colleagues surprised her with an asteroid.

They were at an annual meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in Calgary. Whitehorne, a member of the organization and a longtime science educator, was standing outside of a pub, engaged in a conversation, when a coworker called her inside. He had a special announcement to make: A small asteroid, orbiting between Mars and Jupiter, had been named after Whitehorne.

“I was completely floored and completely speechless,” Whitehorne says.

Whitehorne’s colleagues had waited about two years for the name to be approved. Asteroids can’t be named for just anything or anyone; there’s a careful selection process with lots of rules, managed by an international organization in charge of collecting and sorting observational data for asteroids. The organization is the Minor Planet Center, which is run out of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Massachusetts, and under the purview of the International Astronomical Union, an organization of professional astronomers.

The first asteroids to be discovered, in the early 1800s, were named for figures in Roman and Greek mythology, like Ceres, Pallas, and Vesta. Astronomers ran out of those options fairly quickly, so they started looking elsewhere. Today, most asteroids are named for people, both real and fictional, and the rest for places, animals, plants, and other natural phenomena. The discoverers of asteroids are responsible for proposing the names—but there are rules, and their proposals can get denied.

When a new asteroid is first spotted, the Minor Planet Center gives it a provisional designation composed of the the year of discovery and two numbers. If astronomers successfully study and confirm its orbit, it gets a permanent numeral designation that corresponds with the object’s place on the chronological list of previous discoveries. The discoverer then has 10 years to suggest and submit a name for the object, including a short pitch for why the name should be accepted. A 15-person committee at the International Astronomical Union judges the name and, if it approves, publishes it in a monthly newsletter.

The names should be “16 characters or less in length; preferably one word; pronounceable (in some language); non-offensive; and not too similar to an existing name” of an asteroid, according to the Minor Planet Center’s website.

There are guidelines for certain kinds of asteroids. Objects that cross or approach the orbit of Neptune, for example, must be named for mythological figures associated with the underworld, while objects right outside of Neptune’s orbit get named for mythological figures related to creation.

Asteroids can’t be named for pets, but there’s at least one named for a cat, allowed perhaps because the cat itself was named for a Star Trek character. In 1985, an astronomer received approval to name his asteroid Mr. Spock, after the cat that had kept him company during long hours at work.

Discoverers can’t sell the chance to name their asteroid, but naming contests are allowed. In 2012, NASA asked students to name (101955) 1999 RQ36, a near-Earth asteroid and the target of a robotic mission, OSIRIS-REx, which launched last year. They picked Bennu, for the Egyptian mythological bird resembling a heron.

Whitehorne’s asteroid was among a number of asteroids discovered by three astronomers doing comet surveys in 2004. Her colleagues knew of the trio and their work, and asked them whether they could claim one in Whitehorne’s honor, to celebrate her years of contributions to the field. Whitehorne started out 30 years ago as a volunteer amateur astronomer at a small planetarium in Halifax, her hometown. Not long after, she jumped into astronomy and science education, working with students and teachers and developing programs and curricula for schools across the country. In 2015, she became the first female fellow at the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, a position created to recognize the contributions of long-serving members.

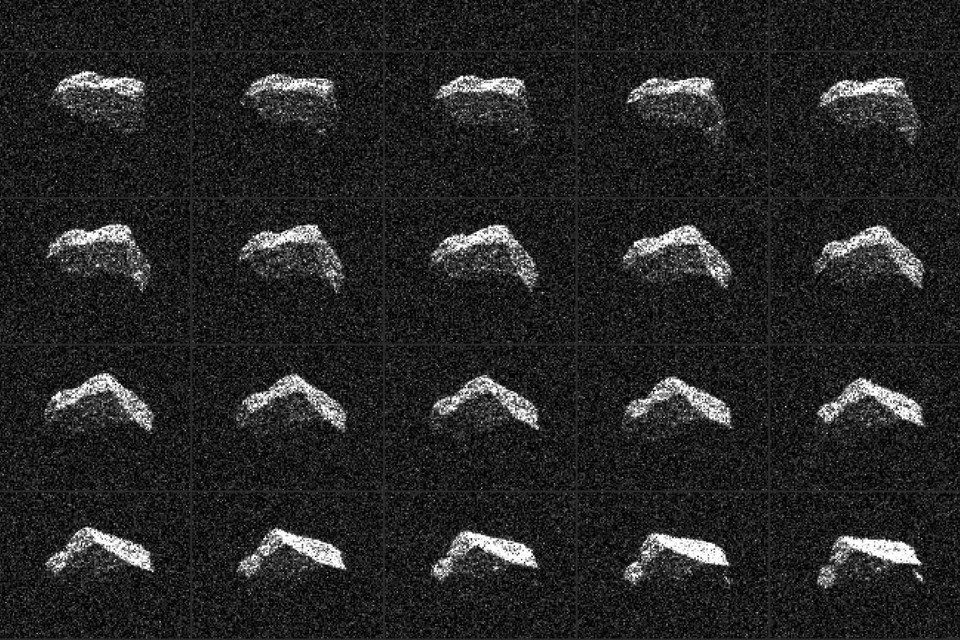

Whitehorne has seen only a photograph of her asteroid, which is about three-kilometers across. It’s too faint to see with her backyard telescope. She calls it her “orbiting tombstone.”

“I am mortal and I am going to die, but my name is going to be on the asteroid as long as there’s human civilization and society on this planet,” she says. “Every once in a while I think about that and think, my goodness, what have I done?”

They were at an annual meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in Calgary. Whitehorne, a member of the organization and a longtime science educator, was standing outside of a pub, engaged in a conversation, when a coworker called her inside. He had a special announcement to make: A small asteroid, orbiting between Mars and Jupiter, had been named after Whitehorne.

“I was completely floored and completely speechless,” Whitehorne says.

Whitehorne’s colleagues had waited about two years for the name to be approved. Asteroids can’t be named for just anything or anyone; there’s a careful selection process with lots of rules, managed by an international organization in charge of collecting and sorting observational data for asteroids. The organization is the Minor Planet Center, which is run out of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Massachusetts, and under the purview of the International Astronomical Union, an organization of professional astronomers.

When a new asteroid is first spotted, the Minor Planet Center gives it a provisional designation composed of the the year of discovery and two numbers. If astronomers successfully study and confirm its orbit, it gets a permanent numeral designation that corresponds with the object’s place on the chronological list of previous discoveries. The discoverer then has 10 years to suggest and submit a name for the object, including a short pitch for why the name should be accepted. A 15-person committee at the International Astronomical Union judges the name and, if it approves, publishes it in a monthly newsletter.

The names should be “16 characters or less in length; preferably one word; pronounceable (in some language); non-offensive; and not too similar to an existing name” of an asteroid, according to the Minor Planet Center’s website.

There are guidelines for certain kinds of asteroids. Objects that cross or approach the orbit of Neptune, for example, must be named for mythological figures associated with the underworld, while objects right outside of Neptune’s orbit get named for mythological figures related to creation.

Discoverers can’t sell the chance to name their asteroid, but naming contests are allowed. In 2012, NASA asked students to name (101955) 1999 RQ36, a near-Earth asteroid and the target of a robotic mission, OSIRIS-REx, which launched last year. They picked Bennu, for the Egyptian mythological bird resembling a heron.

Whitehorne’s asteroid was among a number of asteroids discovered by three astronomers doing comet surveys in 2004. Her colleagues knew of the trio and their work, and asked them whether they could claim one in Whitehorne’s honor, to celebrate her years of contributions to the field. Whitehorne started out 30 years ago as a volunteer amateur astronomer at a small planetarium in Halifax, her hometown. Not long after, she jumped into astronomy and science education, working with students and teachers and developing programs and curricula for schools across the country. In 2015, she became the first female fellow at the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, a position created to recognize the contributions of long-serving members.

Whitehorne has seen only a photograph of her asteroid, which is about three-kilometers across. It’s too faint to see with her backyard telescope. She calls it her “orbiting tombstone.”

“I am mortal and I am going to die, but my name is going to be on the asteroid as long as there’s human civilization and society on this planet,” she says. “Every once in a while I think about that and think, my goodness, what have I done?”

No comments:

Post a Comment