I fixed a lot of fights over the years. In two I didn't fix but should have, people paid heavily for my carelessness. Even though I set up Mitch "Blood" Green and Leon Spinks cushion-soft in their comeback fights, I managed to get one embarrassed and the other nearly killed. There had been opportunities for them, deals that came undone when they lost. It wasn't as if the winners benefited in any tangible way either. At best their victories brought them smallish short-term bragging rights. Among boxing insiders they were objects of scorn for having won, as incompetent at their jobs as Green, Spinks, and I were at ours.

Writing about boxing sometimes adopts a heroic perspective on the sport. This seems especially common in a certain kind of popular journalism. When a boxer gets into the ring, he's seen as entering a magic theatre of virtue and vice cut off from the rest of the world. For the fight's duration his actions assume a kind of moral transparency, defining him as noble or ignoble. But when it's over and he steps outside the ring, becoming just a person again, the aura sticks. To participate in fight fixing therefore defines him morally not only as a professional fighter, but as a person. Lost in this vision of things is any awareness of the way boxing actually works as a business, and the racially and economically inflected cultures within which that business is transacted.

Why did I fix fights? I fixed fights because it was the smart thing to do.

Blood

I started managing Mitch Green in late 1991, a little more than a year before his loss to Bruce Johnson. He'd been a high-profile contenderâ€"an imposing eccentric who'd famously fought Mike Tyson twice, once in the ring and once on a Harlem street, and who with a little work could be brought back into the title picture. Our first business meeting took place at a gimmicky penthouse restaurant in Cambridge, Mass., that revolved slowly above the city. The first thing Mitch did was rise up from the table, peel down the top of his bright orange jumpsuit, flex his pecs, kiss his biceps, and invite a roomful of sedate diners to "feast your eyes on what a real heavyweight is supposed to look like."

This bit of underground theater made me optimistic: Mitch Green could still work a room. But no sooner had the ink on our contract dried than he got shot. While idling on the corner of 129th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem, Mitch slapped a man who'd been baiting him about his fights with Mike Tyson. The guy bolted into his apartment and came back blasting. I still have the blood-stained sneaker, complete with bullet hole. I keep it as a kind of macabre reminder, though I'm not sure of what.

Mitch limped six blocks to Harlem Hospital. He was X-rayed, told the bullet had passed through his leg, given a clean bill of health, and sent home. The attending doctor missed the bullet lodged behind Green's knee. By the time Mitch called me a week later, he couldn't walk. His femur, further traumatized by running and jumping rope, had split like a tree branch. I flew him to Boston, picked him up at Logan Airport, and took him straight to Beth Israel Hospital. The Celtics' orthopedic surgeon, Frank Bunch, had him on an operating table within two hours. If he'd waited another day, Mitch probably would have lost his leg.

During the six months of rehab that followed, Mitch lived at a house I owned near Boston. He regularly demanded cash; had two girlfriends flown in from different parts of the country for what turned into a non-consensual threesome that ended only when my terrified downstairs tenants called the police; sent the "salary" he was getting home to his mother, who spent it on bingo trips to Atlantic City, and complained incessantly. I didn't get it: I was knocking myself out for him and he was doing nothing for me, yet he never stopped complaining.

Visions of Don King and Mike Tyson obsessed Mitch Green, along with those of a number of black civic leaders he believed to be in cahoots with them. It was generally assumed he was paranoid, crazy, and dangerous. But consider: When Mitch was a child in Georgia, his father had been shot dead at point-blank range by a man he was simultaneously shooting dead. The men's funerals were held in the same mortuary on the same afternoon, both families sweating through their Sunday best no more than a few feet apart. Or this: As a gang lord, Mitch presided over New York's Black Spades, a gig that required him to maintain an aura of menace while fending off anyone insane enough to challenge him. Or this: As a young man who'd won the New York Golden Gloves heavyweight title four times in a row, he'd been given money, cars, and an assortment of flashy presents by some of boxing's white elite, like Shelly Finkel and Lou Duva.

After sleepwalking in 1986 through a 10-round decision loss to Mike Tyson, held in Madison Square Garden and shown on HBOâ€"for which he received $30,000â€"Green met his nemesis again on the street. Their brief, violent encounter made headlines. Afterward, Green dropped off the boxing map.

My job was to bring him back. Smarter men than I said it was impossible. Signing up Mitch Green even earned me 1993's "Sucker of the Year" award in Boxing Illustrated. The only money Green ever made me came from betting Al Braverman, Don King's director of boxing, that I'd be able to coax him back inside the ring.

I was sure I'd picked the right foil for Green's comeback match. A gangly, knock-kneed cruiserweight, Bruce Johnson came in with a record of 8-22-1. He'd been knocked out 17 times and had never beaten a credible opponent. Johnson always arrived from out of town prepared to lose. His livelihood depended on his career going nowhere.

In the dressing room, Bruce told me he was afraid of Mitch Green, then held me up for $500 more than the price we'd agreed on. All I would have had to say for Mitch Green to win was: "You want five hundred more dollars? Get knocked out by the third round."

I didn't do that. I didn't think I needed to. Mitch Green was going to kill him.

But in a tiny arena in Woodbridge, Va., on a frigid winter night when a blizzard reduced the house to nearly nothing, Mitch Green, angry that he wasn't getting paid enough or being properly respected, got into the ring and refused to throw or block punches. Johnson was never on his radar. Mitch ignored his feeble jabs. He also ignored me, my partners Pat and Tony Petronelli, and everything but the private buzzing in his head, gazing stone-faced over Johnson's shoulder into the middle distance. After several warnings from the referee to start punching or risk having the fight stopped, the plug was pulled in the third round as the handful of spectators hooted. Mitch "Blood" Green had thrown his future away in less than nine minutes.

I wouldn't talk to Mitch Green after that. I'd lost a year of my life and $80,000 on him.

The Foolproof Opponent

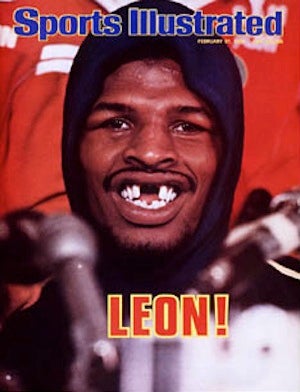

I never intended to manage Leon Spinks, the free-wheeling heavyweight who'd upset Muhammad Ali in 1978. I was interested in his sons Darrell and Tommy and their fellow East St. Louisan Freddie Norwood, and that entailed looking out for Leon, too. It wasn't until he lost a decision in North Carolina to Eddie Curry, a dive artist who could fight a little if no one told him not to, that I got roped into actually managing him.

That night Leon and Curry quickly bogged down into a slow grind, their mutual lack of conditioning forcing them to drape themselves over each other in a sodden ring where the temperature was over a hundred. Leon hung in on heart; Eddie, with the dawning realization that he was going to get a win over a former heavyweight champion.

But Spinks caught two lucky breaks: For one thing, Eddie Curry was being paid by the round; for another, I'd done previous business with Bobby Mitchell, the South Carolina commissioner brought in to oversee the card, who also happened to be Curry's manager. After eight rounds, under the impression that he'd gone the distance, Curry demanded that his gloves be cut off. Feeling a sense of responsibility to Leon, who was only fighting to help his sons, I climbed into the ring and told Mitchell the fight had to continue: The fight poster listed the main event as a 10-rounder.

But not even the judges were aware. The decision had already been announced for Curry, and he refused to put his gloves back on.

In the center of the ring, I made some noise: "It's a 10-round fight. You've got one minute before the next bell rings. Better get Eddie's gloves back on."

"The fight's over. The decision's been announced."

"It's been announced to 300 people who'll never check the record book."

Mitchell conferred with Curry.

"Eddie, this is your night. Spinks is an old man."

"No way. I ain't fightin' no more."

I butted in. "Thirty seconds before the next round. Let's go."

"OK, I see what you're doing. Can we talk about this in the office?"

"Absolutely," I said. "I just need it to go into the record books as a win for Spinks. Does Leon win the fight?"

"Shit, yeah. Leon wins the fight. But do we have to take care of it here?"

So Leon Spinks got his win, and I got stuck with Leon Spinks.

I had no idea what to do with him. He couldn't fight. The only interest promoters had in him was as a small notch on some young killer's belt. Then an unlikely offer to fight Larry Holmes in China popped up. It wouldn't pay by the standards of Leon's brief heyday, but it was a hundred times more than he was getting for his current fights. I was sure I could get Holmes to listen to reason. Years earlier, in defense of his heavyweight title, he'd mercifully knocked out a much better Leon Spinks in three easy rounds.

But before the Holmes fight could be madeâ€"even as far away as Chinaâ€"I had to put Leon back in the public eye. That meant a high-profile venue where he could conspicuously knock someone out. I landed him a main event at the Washington D.C. Convention Center.

To get Leon on the cheap, the promoters, a small group of street-smart local hustlers raising money for Marion Barry's re-election, let me bring in my own opponent. But my fall guy came up with a bad CAT scan and the D.C. commission rejected him. I was stuck scrambling for a replacement.

John Carlo had never fought before. No commission would sanction a fight between an ex-champ, however diminished, and a debuting boxer who didn't have the equivalent of an Olympic pedigree. Online records had made it impossible to invent wins and losses in any commissioned state, so I had to falsify Carlo's entire professional career by staging his "fights" in non-sanctioned states. I imagined him as a journeyman with a respectable 13-2 record. For opponents I chose the names of real fighters, habitual losers who often fought in unregulated states. Even they wouldn't remember whether or not they'd lost to a John Carlo. But after these elaborate maneuvers to provide Spinks with a foolproof opponent, I failed to take the one step needed to guarantee the result: I didn't fix the fight.

John himself brought it up. A couple of days before the fight, he asked, "What happens if I win?"

We both laughed about that.

"If you can beat him, beat him. If Leon can't handle a guy who's never been in the ring before, he has no business being there. You'd be doing him a favor."

A few seconds after the bell rang, Leon extended a brotherly right hand to John Carlo, intending to touch gloves. But Carloâ€"intense fear producing the effect opposite of what I'd expectedâ€"was not in a collegial mood, first feinting and soon following through with a viciously professional left hook that felled the former champ as if he'd been nailed by a 10-pound mallet. Spinks dropped straight back, his head bouncing audibly off the canvas. He barely beat a very slow count, and Carlo was on him in a delirium, dropping him again. A minute later the fight was over. So were any thoughts of Larry Holmes, China, or the $175,000 Spinks would have made fighting someone skillful enough not to hurt him.

The Art Of The Fix

No sport is romanticized more than boxing. Heroic writers use boxing to make moral sense of the world. Noble fighters, by their actions, stabilize chaos: Their bravery in the face of untenable circumstances and violent hostility helps to restore value and security to a now-intelligible world, one inhabited by heroic journalists and their readers. Heroic journalism attaches a sentimental narrative to the rise of a title-holder, carving out a cinematic character arc wherein horrific circumstances are overcome through moral probity, grit, hard work, and determination, and climaxing with HBO viewers themselves choking up a little as the victor tearfully accepts his championship belt after winning a brutal encounter at Caesar's Palace.

Winning a world title is definitely hard, time-consuming work, so that kind of arc expresses some truth. What it obscures is the fact that most of the fights designed to get that fighter his title shot are fixed in one way or another. Anybody who spends his own money advancing a fighter and knows what he's doing engages in some form of fight fixing. And, wittingly or not, almost every titleholder has benefited from fixes.

A former president of the Boxing Writers Association of America once said, "When it comes to sports, all a writer needs to know is how wonderful it feels to win, how miserable it feels to lose, and how hard it is to try." If you get paid to write about boxing and believe this, the kindest thing that can be said about you is that you're a sucker.

I see boxing differently now than when I was managing fighters. Starting out, I assumed that an encyclopedic knowledge of the sport as art was all I'd need to handle the careers of professional fighters. I didn't manage opponentsâ€"my clientele was made up of champions, contenders, and prospects. I thought champions should be matched with contenders whom they'd beat, contenders should be matched with tough journeymen whom they'd beat, and prospects should be matched with lesser prospects or former champions or contendersâ€"whom they'd beat.

I could pick the winner of a fight more than 90 percent of the time, and I thought this was a unique talent. I didn't know that nearly everyone in boxing could do it; those who can't, hire someone to do it for them. Boxing's political factions and complex, shifting hierarchies were also largely unknown to me.

In fights that aren't fixed, even well-informed mismatches can go awry. Personal problems, off nights, jealousies, injuries, internecine conflicts, double-crosses, hometown decisions, promotional affiliationsâ€"all can throw a monkey wrench into the most carefully laid of plans.

Despite my careful matchmaking of another fighter, Martin Foster, I watched him go from an undefeated heavyweight whose only real asset was his reliable chin to a sure kayo victim whose knees would sag and whose eyes would roll into the back of his head whenever he was tagged solidly.

This transformation took place over a matter of months. Finally, on a Don King card in Belfast, Ireland, Foster lost in a way that was chilling enough for me that I no longer wanted to be even partially responsible for his further participation in boxing.

Fighting the light-punching Frans Botha in a heavyweight title eliminator, Foster had his nose erased from his face by a bolo punch that everyone in King's Hall but he saw coming. It was such a sucker punch that Botha, who'd wound it up theatrically, started laughing. And then, still laughing, he did it again. And it landed again. As Foster began to sag to the canvas, the referee rushed in to save him. His cornermen, Tony Petronelli and Chuck Bodak, and I half-carried Martin down the ring steps and across the large auditorium to his dressing room. It took Chuck nearly a half hour to get Foster to spit all the blood from his broken nose into a bucket. By the time he was done, the bucket was fuller than it would've seemed possible.

Martin Foster owed me a lot of money at that point. But when we met at the airport the next morning to fly to different parts of the U.S., I told him that I'd forget about the debt if he promised to retire from boxing. He had a wife and two young kids, and I was aware that somewhere down the lineâ€"in five or 10 yearsâ€"they were going to lose some of him even if he never took another punch. I was clear: If I found out that he'd returned to fighting, I would come after him and collect my money.

We shook hands on it, then went to our separate planes. I never saw Martin Foster again. When I got Don King's paycheck for the fight, I kept all of it.

After I stopped managing Martin, he was knocked out 11 times in 12 non-fixed losses, no doubt resulting in much additional damage.

Boxing managers have an obligation to minimize the amount of damage their fighters sustain. By the time any fighter gets a shot at a championshipâ€"usually his first opportunity to make real moneyâ€"he will already have had very hard fights and been banged up in ways that will not yet be outwardly apparent to most people. His career is likely to be halfway over. If he becomes the champion, most of his title defenses during the next few years will be tough ones. If he fails in his title attempt, depending on the nature of his performance, he'll either get more chances or be demoted to the rank of "name" opponent. If he's lucky enough to get more title shots, none of them will be easy. The market demands that they not be: As a known loser, he's no longer entitled to have the path eased for him. Once he's slipped to the role of opponent, he'll get beaten up repeatedly, his purses and his health diminishing with each successive loss. And at this point, the fighter will most likely be looking at a post-career future of neurological impairment. He may have four or five real earning years left to him.

These are hard facts, but they're almost unfailingly representative of what a "successful" fighter can expect. Why should any fighter take the punishment that this profession brings, if not for money?

The most responsible way to develop a new fighter is to combine easily winnable fightsâ€"albeit ones that require some of his attention and skillâ€"with fixed fights that will move him quickly up the ratings. The goal is to earn a fighter as much money as possible without incurring unnecessary wear and tear. He'll have to be in enough tough fights when the time comes.

Fight fixing is such an accepted part of the boxing business that there's a standard way to do it. You call up or visit the gym of any trainer who represents "opponents," and have the following exchange:

"I've got a middleweight who could use a little work." [Read: His fight shouldn't be more than a brisk sparring session.]

"I got a good kid. But he ain't been in the gym much lately." [He's out of shape.]

"That's OK. I'm not looking for my guy to go too long." [It's got to be a knockout win.]

"My kid can give him maybe three good rounds."

And that's it. Your fighter's next bout will go into the record books as a third-round knockout victory.

Your guarantee that you'll get the result you want is simple: Guys who deliver opponents have to earn a living. If their fighters win, they won't be able to do that. On occasions when an opponent realizes victory is within his grasp, his trainer reminds him that getting fresh will prevent him from being paid. If this doesn't work, the trainer stops the fight in the corner after the agreed-upon round. "I have to watch out for my kid," he laments. "He was taking too much punishment" or "His leg cramped up" or "Jeez, I can't explain it. The kid just quit on me. And he was doin' so good." He shakes his head sadly.

I've arranged for countless such endings. I've bought off referees and commissioners. I've simultaneously managed fighters from both corners. I've picked up the tab for entire fight cards, effectively guaranteeing that the judges were in my pocket. While standing a foot from ringside, I've had kayoed opponents wink at me as they were being counted out.

Unfixed

There was even an occasion where what was supposed to be a fixed fight turned into a real one. It was 1994. I was looking to bring former WBO cruiserweight champ Tyrone Booze back into contention as a heavyweight. To do this required his scoring a series of quick knockouts. I had a deal going in Raleigh, N.C., where every couple of months I would fly down with the winning half of the fight card. The local matchmaker would provide the homegrown losing half or I could bring one of my own.

This time around, Booze's intended victim was Marc Machain, a keg-shaped brawler from the trailer parks of rural Vermont. "The Rutland Bull" stood 5-foot-7 and weighed 220 poundsâ€"only a few of them fat. Machain was a sentimental, happy-go-lucky guy who loved to fight, whether he was landing or taking punches. His favorite type of fight was when he got to do both. In the past he'd worked for me as sparring partner; I knew he'd never beat Tyrone Booze in a legitimate fight. But he might take him the distance, with the two guys banging heads and exchanging elbows and low blows for the whole 10 rounds. Even in nothing fights, it's inevitable that heavyweights will do damage. If there's a way to minimize injuries, you're foolish not to use it.

I explained this to Marc Machain. "Have fun in there," I told him. "Give Tyrone five or six rounds, then I'll have Tony stop it in the corner."

The Rutland Bull reluctantly agreed, and we had a deal. I thought we had a deal. At the time we made it, Machain undoubtedly thought so, too. He was an honorable man.

If you hadn't spent time around tough guys, you wouldn't peg Tyrone Booze as one. He had a round head, tiny amphibious eyes, sloping shoulders, and a layer of fat that no amount of training could remove. He smiled often and laughed easily. His voice was deep, but swooped up to a falsetto "whaaat?" when someone's behavior surprised him. When he was tired, he sometimes slurred his words.

Tyrone was an original thinker who knew everything there was to know about the boxing business except how to make money in it. He had spent his career losing competitive and occasionally unjust decisions, one after another, to the animals no one else would fight. He had fought eight world champions, including Evander Holyfield, Dwight Muhammad Qawi, and Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, without having been off his feet against any of them.

Still, I had to be persuaded to manage him. He had too many losses, and he almost never knocked people out. But Floyd Patterson, who trained some of my fighters, thought something could be done with him. And then later, when Booze went to Las Vegas to work as chief sparring partner for Riddick Bowe, I got a surprise phone call from Eddie Futch, asking if he could train him. He'd been impressed with how Tyrone handled himself against the heavyweight champ. Bowe had gotten a little out of line, so Booze had ducked his shoulders, plowed into him, and tossed him over his head onto the canvas. You didn't fuck around with Tyrone Booze.

In his dressing room before the fight, Booze was queasy. His last ring appearance had taken place 17 months earlier in front of over 10,000 people in Hamburg, Germany, where he lost his WBO cruiserweight title to Markus Bott. He'd been characteristically placid before and after the fight. It was nothing to him to fight big-name opponents in hostile territory. When he fought Evander Holyfield on NBC, he'd spent part of the fight laughing at him, waving him on.

But here in Raleigh, fighting in front of 400 people in a dilapidated theater called the Ritz, Tyrone Booze was becoming slightly unhinged. He couldn't settle down. He tried to lie down on the couch, but wound up bolting from the dressing room, walking the hall and back. We couldn't get him to work up a good sweat. He suddenly had chills. His stomach was upset, and he was thought he was going to be sick.

"Man, I don't know why I feel like this. I can't get loose. I mean, I was cool when I fought Bert Cooper. Bert Cooper. Didn't nobody punch like Bert Cooper. And I got to worry about this fat little white boy? He ain't nobody to be afraid of."

Tyrone Booze wasn't afraid of anybody. Or anything. None of this came from fear. Tyrone Booze was unable to process getting back what he'd lost when he'd stepped away from boxing.

More than almost any other activity, boxing forces and keeps you squarely in the center of each moment. To box requires you to be dynamically alive, to be alert to every possibility. Lapse for a moment and you'll get knocked out. Anything less than complete absorption might even get you killed. Once you've grown used to that degree of vitality, it's hard to withdraw from it.

If professional fighters really do fight primarily for moneyâ€"and they doâ€"it would be naïve to dismiss the existential elements that bring them back to the ring once their money is gone. Booze wouldn't have returned to boxing if there hadn't been a promise of big paydays soon, but what was knocking the shit out of his system was the inchoate elation of knowing he was able to get back in the ring.

As a rule, you don't tell the intended winner of a fixed fight that the outcome is rigged. It causes him to fight unnaturally, and the fix is easier to spot. But Booze was an old pro; I felt OK telling him to go easy. And I liked Machain. Durable as he was, I didn't want him to have to take too much of a pounding for his thousand dollars.

I brought in seven of the eight fights on that night's card. Besides Booze, future middleweight champ Keith Holmes and Olympic gold medalist Andrew Maynard got wins: pearls before swine. The Raleigh crowd, mostly drunken rednecks, was a universe away from seeing world-class fighters except when I brought them. They were yahooing with mayhem after a night of emphatic first- and second-round knockouts. For the main event, they were itching for something longer and more punishing; a decisive early knockout wouldn't do. They wanted to see a couple guys beat each other up in a slugfest. Somehow this collective longing found its way up into the ring and imprinted itself on the two fighters waiting for the opening bell. Standing at ringside just below Booze's corner, I had an inkling that things might become unruly.

The fighters tried to do what was expected of them. At least for the first two minutes they followed the script. Then Booze caught Machain walking in and buckled his knees with a right uppercut. I don't think he intended to hit him so hard. It was a combination of training, muscle memory, and a sudden access of adrenaline. I could see Machain was badly rattled. He smiled at Booze. He said something through his mouthpiece; I couldn't make it out. He banged his gloves together. He threw a wild overhand right that missed by a mile. It sent a complex message: I'm still behaving, but don't try that shit again.

But it was more than that. There was an invitation in the punch. I could see it. The bell rang, and that's when I think the two of them decided to fight as hard as they could. They knocked gloves enthusiastically. Machain said something to Booze. Tyrone laughed.

In the second, I could see it was not going to be the sparring session I'd asked for. Marc Machain pressed forward, fighting out of a crouch, trying to come in under Booze's headhunting shots, hoping to bang to the ribs, occasionally throwing haymakers at Tyrone's nicely tucked-in head. He succeeded just enough to keep himself in the fight, and keep the fight exciting.

Meanwhile, Tyrone was having a party. If you were going to make a real fight for him, it would be hard to pick a better opponent than Marc Machain, who constantly waded in with no concern for being hit, his gloves wide apart, his chin jutted defiantly forward. Booze teed off with uppercuts as the crowd oohed and "oh, shit!"-ed. There was now an audible black contingent in the house. I started hearing the word "nigger" coming from both white and black voices, its meaning dependent on who was using it.

The first knockdown, predictably from a right uppercut, came late in round two. Booze placed it perfectly, nailing Machain under the chin as he came in, flooring him suddenly. Machain dropped in a heap at Booze's feet. I thought he was finished. He shook his head, trying to clear it, and worked his jaw.

Then, to my dismay, he got up.

At that point, I might have been able to signal to Tony Petronelli to throw in the towel. People would have bought it. I didn't do that. I looked at Tyrone Booze waiting in the neutral corner. He wanted to fight. Machain signaled to the ref that he was OK. He wanted to fight, too. The crowd wanted them to fightâ€"rednecks and blacks alike. I thought, "Everyone wants the fight. Fuck it, let them fight."

For as long as it lasted it was a good fight, for the crowd. It had the appearance of give-and-take, although it was actually one-sided. Because Machain continued to come forward (except when he was being drilled with uppercuts), he gave untrained viewers hope for a miracle. They were true believers, as was Machain himself, who felt that if he landed just one haymaker, he could end things. Except that Marc Machain didn't actually punch very hard. And Tyrone Booze had absorbed, without flinching, the hardest punches of the hardest punchers of his era.

I settled in at ringside and allowed myself to become entertained by the fight. Booze was working off ring rust, getting his timing back, putting in some rounds. Machain was having the time of his life getting the shit kicked out of him.

Toward the middle of round five my business sense returned. Even though the fight was one sided, it had become predictably rough. Booze hadn't knocked Machain down again, so there hadn't been a "right" time to stop it. I started to worry whether Tyrone could score the knockout he needed.

I was about to walk to Machain's corner to let Tony know his fighter would need to be diagnosed with either a shoulder injury or a broken jaw (either one would require that the fight be stopped) when the end came.

It was the same uppercut that caused the first knockdown. Booze's punch was just as perfect, but no harder. Machain, if anything, took it better than the first one, since he was now warmed up. But he again got dropped hard, and I only had to look over to his corner to get Tony Petronelli started into the ring.

"Oh, no," Machain wailed, "I'm OK, I'm OK." He put his gloves up in fighting stance. Tony was leading him to his corner, pulling out the mouthpiece.

"Aw, Tony, why'd you stop it? I was having fun! Nobody wants it stopped."

He was right. Mostly right. I wanted it stopped.

After it was over, the two fighters sat at a table at a Denny's across from the Ritz. Machain was banged up a little. Not too badly. Booze was fine.

Now ravenously hungry, wolfing down mountains of starchy, sugar-coated, butter- and oil-dripping fast food, Booze and Machain were still giddy from the fight. Effusively complimentary, talking with their mouths full, they relived every detail of what had just taken place.

"I couldn't believe you was gettin' up from them uppercuts, man." Booze shook his head in admiration.

"I couldn't believe how you kept catching me with them."

"That's 'cause you was walkin' straight in. You don't never move your head."

"I got a hard head."

"It's true! It's true. You do got a hard head. But I was timin' you, man."

"I know. You timed me good."

The 89th Second

The best fixer I ever knew was Vin Vecchione. In the 1990s we spent a lot of time together, making big plans, drinking bad coffee in cheap diners, laughing at our friends and enemies, forging boxers' medical records, and getting our fighters wins.

Vin died suddenly in 2009. I'd left boxing and we'd lost touch. But I wanted to see how Peter McNeeley was doing, so I went to the memorial service. The embalmer had done a lousy job: Although still clutching a cigar, wearing his cap, and smiling his secretive half-smile, Vin didn't look like anyone I'd ever known or anyone who'd once been a person.

When I met Vin in 1993, I was managing an undefeated heavyweight I'd brought to Brockton from the Midwest. Vin handled McNeeley, also undefeated. I'd agitated on local radio shows and in newspapers for a showdown. Vecchione called to request a sit-down at a local luncheonette. When I arrived, he draped a hefty arm around my shoulder, walked me to a booth, helped me off with my overcoat, and sat down across from me.

"My fighter ain't never going to fight your fighter. OK, we got that outta the way. Now we might as well get along."

Two years later McNeeley would last 89 seconds against Mike Tyson in what was then the largest grossing event in sports history. The fight ended when Vecchione nonchalantly slipped between the ropes to save his still-standing fighter.

There were two journalistic responses, both outraged. The first was based mainly on a perceived attack on the sanctity of the sport: People had paid big money to witnessâ€"depending on their temperamentâ€"a fight or a slaughter, and had been euchred out of seeing either. McNeeley was still OK when referee Mills Lane waved things off. And though he was in some trouble when the fight had ended, it wasn't a sure thing he was finished. Boxing writers pointed out that McNeeley hadn't "gone out on his shield." Soon after the fight's conclusion, he could be seen walking around the ring with an outsize grin on his face, chatting with reporters, family, and friends, his distress wearing off by the second. Paid nearly a million dollars to serve as a human sacrifice, he'd escaped without a bruise.

The second response didn't show up until the fight narrative had passed through a series of plausibility tests and been green-lit as acceptable. This version featured McNeeley fighting valiantly ("He charged right at Tyson!"), and being inexplicably robbed of glory by Vecchione. As Ferdie Pacheco stammered, "He doesn't belong in boxing if he's going to save his fighter." Vecchione had cheated both Peter and the public.

But Peter McNeeley, if not expertly maneuvered, would never have gotten nearly as far in boxing as he did. Vin earned McNeeley a $700,000 payday, pushing the figure to over a million by parlaying the fight's weird conclusion into two lucrative TV commercials and keeping the door open for Peter's ongoing viability as a high-priced opponent.

Granted, Vecchione wasn't thinking only of his fighter's welfare. Vin's payoff wasn't limited to the fight purse. The real money was in knowing exactly how Peter McNeeley would do fighting Mike Tyson. And Vin knew down to the second how Peter McNeeley would do.

The night before Tyson-McNeeley, someone in Las Vegas placed a million-dollar bet on the fight not going a full 90 seconds. When Vecchione, seemingly unhurried, stepped between the ropes to force an automatic disqualification, 89 seconds had elapsed.

I didn't know it was going to happen. Vin and I had gotten together in the dining room of a Braintree, Mass., hotel just prior to his bringing McNeeley to Vegas and my heading back to my place in Puerto Rico. He'd said then that no one had approached him about having McNeeley take a dive. But later two strange things happened. I got a phone call from someone I didn't know well. This person mentioned that a private million-dollar bet had been made that the fight "wouldn't get past the first round." Soon after the fight, Vin called to ask if I'd come to his house to pick something up. I was still in Puerto Rico, so I asked if I could send someone. Vin said, "Send someone you trust." When my guy met with Vecchione, he was given an envelope that contained enough money to put my son through college (admittedly, an inexpensive one).

I've often thought about the kind of discipline that must have taken, the Zen-like calm of a small-timer who could wait and wait, during the biggest money event in sports history, until there was literally not another second to wait. I've marveled at the ingenuity of Vecchione, planning ahead for years with no budget and no promise of good things to come, slowly and steadily bringing this move to its amazing conclusion.

He'd considered every angle. Vecchione knew that for all its posturing the Nevada State Commission would have to pay him: Tyson was the biggest cash cow in the state's history, and any problem with the fight's outcome would gum up a billion dollars in future casino business. Vin had the state of Nevada, the casinos, the commission, pay-per-view boxing, and Don King by the balls, and he knew it.

A heroic narrative painted Tyson as a savage warrior from the mean streets of Brownsville and McNeeley as a soft white boy from suburban Medfield, Mass., who hadn't earned his shot. But Tyson had been a multimillionaire for his entire adult life. McNeeley and Vecchione were a couple of hungry motherfuckers who didn't have a dime between them. Had McNeeley been a more accomplished fighter, he would have torn apart the easily discouraged Tyson. And Vecchione would have had to figure out some other reason to step into the ring early.

The "What We Gonna Do Now?" Present

Even if they don't agree with it, almost anyone can understand the case for fixing a fight to keep a fighter from being unnecessarily hurt. Fixing one to get him paid might seem like a tougher sell.

According to the heroicizing ethic, boxers should fight only the toughest possible opponents, engage in fair play, maintain the moral integrity of the sport, perform courageously, make sure the fans get their money's worth, and not flaunt their success unduly. From this perspective figures like Roy Jones and Floyd Mayweatherâ€"or before them, Ray Robinson and the pre-hegemonic Muhammad Aliâ€"are seen as agitators who have no business making rules for themselves.

In the same vein there is the argument that boxers choose to participate in their matches, that they're aware of the chances they take every time they step into the ring. Well, yes and no. There's a difference between knowing that you can be maimed or killed in any particular fight and understanding how over a period of time you will in all likelihood sustain irreversible damage. The signs of this damage can be obvious but they can also be subtle, invisible to boxing outsiders. Any punch-drunk professional fighter can still duck under the ropes and kick the shit out of you or me.

For managers, boxing is a business. The meter is running from the moment a fighter's contract is signed, if not sooner. Bankrolling a stable of winning fighters takes deep pockets. The sparring partners, as well as the winners, need to eat. They all need places to live, have families to care for and bills to payâ€"whether or not they have promising futures.

My former business partner Pat Petronelli and his brother Goody became multimillionaires managing middleweight champion Marvin Hagler. Pat ran his stable like a feudal system. Fighters were told whom, when, and where they'd be fighting and what they'd be paid. Pocket cash was doled out in whatever increments he thought best. If a fighter needed to stay in Brockton between fights or while working as a sparring partner for Hagler, Pat would put him up at a rooming house run by Marvin's aunt Herbertine Walker. Herbertine rented out cheap, clean rooms, cooked healthy meals, and provided laundry services. She ran a tight ship; if you stayed at Herbertine's you stayed in line.

Except for the conspicuous presence of crack users and dealers, walking from the gym to Herbertine's boarding house was like being in Birmingham or Mobile during the 1950s. The neighborhood was entirely self-contained. Barbershops, variety stores, bars, barbecue shacks, laundromats, and beauty salons crowded together. It was known to be a dangerous area, but walking through itâ€"hearing talk and laughter, music pulsing from storefronts and boom boxes, smelling the competing scents of fried food wafting from the fast-food jointsâ€"didn't seem oppressive. In neighborhoods like this, where the only victories available are very small ones, victories show up everywhere.

It was as if everyone in the neighborhood were operating under a different existential system than I was. Life was defined by the "What We Gonna Do Now?" present or the "After I Hit My Number Tomorrow" future. Those were the choices. The fighters lived on what some of them called "nigger time," an imprecise measure, a vague approximation of when an event might or might not take place. It was time largely outside the volition of those remanded to it.

Boxing is a business for boxers too.

Boxers are born poor and they usually die poor. For their short spell in the business, they inhabit a place in its professional hierarchy that all but guarantees they'll remain poor even during their active careers. Boxers often can't negotiate or even understand their own contracts. Of course, most contracts are unintelligible except to lawyers, but boxers typically have little education and are often functionally illiterate. Many fighters turn over the exclusive rights to sign their contracts to their managers. I'd never have managed a fighter whose contracts I couldn't sign or whose purse checks couldn't be made out to me.

All in all, it isn't surprising that boxers operate under a different system from the people who make money off of them or who watch and write about them. In the real world, boxers and their managers pre-arranging the outcome of fights, working collusively against a hostile system, makes sense. Fixing fights, even at the expense of the public, isn't just good business. It's a survival strategy for the disenfranchised class in boxing: the fighters themselves.

I got out of the business in the latter part of the 1990s. It would be a good story to say that I had a moral epiphany that lifted the veil from my eyes. That wouldn't be true, though. I got involved with some dangerous people, and some bad things happened. So I left. Over time, I've come to see boxing differently than when I earned my living from it. I've learned that, in boxing, damage isn't just possible or likely; it is nearly inevitable. I continue to love the art of boxing itself. But, nearly 20 years removed from it, I still find the works of the businessâ€"the larceny and the bullshit and the wheeling and dealingâ€"the most difficult and absorbing thing I've done in my life.

Indian Summer

Another thing that happened in the real world, the day after the the Spinks-Carlo fight.

It was an uncharacteristically hot afternoon for D.C. in late October. An Indian summer, I guess. I was sitting in the coffee shop of the Courtyard Marriott, directly across from the convention center, talking to someone I knew. The night before had been a fucked up one for a number of people, myself included. None of us had lost money directly, but what had happened would keep us from making money.

Leon came across the lobby to where we were sitting. He kept himself at a slight distance, making his presence known, but not interrupting.

I said to my acquaintance, "Have you met Leon?"

"No, but I'd like to."

I introduced the two men. They shook hands. Once Leon had been introduced, he felt freer to talk to me.

"Mr. Farrell, I want a rematch. I do better next time. You get me a rematch?"

"No, Leon. No rematch. I'm sorry."

It was uncomfortable. Nobody knew what to say.

Leon, who'd taken a seat after being introduced, got up and started to move away.

"Can I get some money for something to eat?"

"The promotion is picking up the tab for the hotel expenses," I said. "Don't you want to eat in the hotel?"

Leon looked uneasy.

"OK, no problem. How much do you need?"

"I don't know. Can I get five bucks?"

I handed Leon some money and we watched him go outside.

Charles Farrell has spent most of his professional life moving between music and boxing (with a few detours along the way). He has managed five world champion boxers and has 30 CDs listed under his name. Farrell is currently at work on a book of essays about music, boxing, gangsterism, and lowlife culture; a boxing anthology edited by Mike Ezra and Carlo Rotella; and a TV series, Red House, based on events from an earlier part of his life.

Art by Jim Cooke.

No comments:

Post a Comment