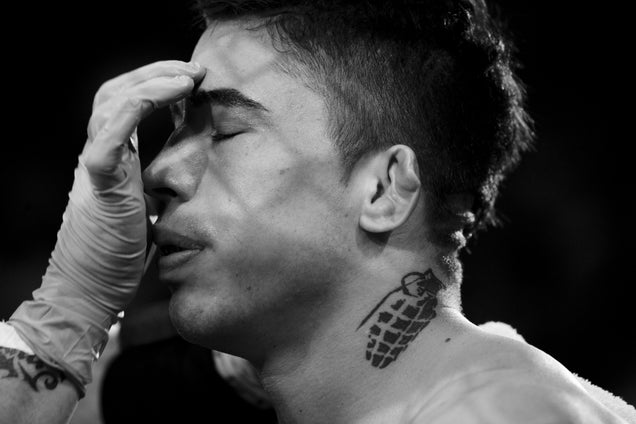

No one needed to see Marlon Moraes continue beating on Josh Rettinghouse. Moraes had outclassed his opponent in every facet of the game for 15 minutes, piling on abuse and bludgeoning his lead leg. Rettinghouse could barely support his own weight, let alone continue to defend himself, and as he hobbled back to his corner at the end of the third round, you could only hope that someone would stop this. As anyone watching Marlon Moraes fight Josh Rettinghouse on a World Series of Fighting card would know, though, that just wasn't going to happen.

Rettinghouse got off his stool and answered the bell for the fourth round. No one stopped him; he's a professional fighter, and like most others is probably far too tough for his own good. He fought for 10 more minutes, hopping and scooting and doing whatever he could to survive to the bell. The ringside doctor and the referee, supposedly there to protect the fighters, and the people in Rettinghouse's corner, who presumably know him and care about his well-being, all decided that this was OK. This was not OK.

Moraes, who seemingly could have turned up the pressure and put the fight away, seemed truly uncomfortable. He coasted through the final rounds, playing it safe and looking almost disconcerted. The announcers lauded Rettinghouse's Do You Want to Be a Fucking Fighter Warrior Spirit. One of them may have even nominated a 50-44 mauling as a possible fight of the year contender.

What's more disturbing than the fact that this happened is that it happens all the time. This wasn't even all that bad, comparatively speaking. Fighters in similar situations are often even less able to defend themselves, and frequently take far more blows to the head.

Mixed martial arts has a problem, a fundamental defect for which doctors and referees, coaches and corners, promoters and announcers, and journalists and bloggers and fans are all responsible. It needs to change.

Fighting is inherently dangerous. We're obligated to mitigate that danger as much as possible. We're doing a piss poor job.

Last week, the American Journal of Sports Medicine published a study on head trauma in MMA. There were a lot of problems with itâ€"knockouts don't work as proxies for brain injury nearly as well as the authors would like them to, they came to a totally unfounded conclusion about the relative safety of boxing and MMA, etc.â€"but as a descriptive document, it was unnerving.

On the basis of a review of fights on numbered UFC cards from 2007 through early 2012, they concluded that the average time between a knockout and a fight actually ending was 3.5 seconds. Fighters, on average, took an additional 2.6 strikes to the head after a knockout. Even worse, in its way, a corner or doctor stopped only seven fightsâ€"just a touch over one per year. This is a problem.

Due to the nature and rules of mixed martial artsâ€"fights can end at any moment due to a submission, a knockout, an incapacitating shot to the body, a cut, an injuryâ€"everyone always has a chance in theory. (This does a lot to explain why referees, doctors, and corners allow cashed-out fighters to keep going.) In reality, that chance is often statistically insignificant. And even when a marginal chance does exist, someone is supposed to weigh it against the damage a fighter is taking. There are reasons why commissions have the power to veto lopsided mismatches, and why referees, medical professionals, and corner men all have the power to say, at any moment, "That's enough."

The problem is that no one likes to see "premature" stoppages, like those in Renan Barão's and Ronda Rousey's recent title defenses. No one wants to be responsible for depriving a fighter a of chance at victory, which can impact their money short-term and their entire career long-term. No one wants to disappoint a raucous crowd demanding carnage and screaming, "Let them fight!" It needs to be done regardless. This may be a difficult thing, a responsibility few would want, but it's what you sign up for when you become a ring doctor, referee, or corner. Most of these people seem to have forgotten that this responsibility even exists.

Josh Rettinghouse was a massive underdog. He never legitimately threatened his opponent through three rounds, and was beaten soundly in each one. Crushing legkicks rendered him unable to walk. He may have had a puncher's chance, but it was vanishingly small. He was done. His sport needs to embrace the fact that there was no reason for this fight, or any fight like it, to continue.

While other combat sports face similar issues, and deal with them poorly, they tend to display some vague awareness that violence has consequences. (Boxing people, especially, know that their sport has been and continues to be a goddamned tragedy.) From top to bottom, though, many people involved in MMA don't.

Some of this blissful ignorance is due to the relative youth of the sport. We haven't had to face its true consequences, because we haven't yet seen what time does to 70-year-old former fighters. In part, the problem is due to the fact that many fans, stuck in a defensive posture, simply refuse to acknowledge the health hazards inherent in full contact fighting. One of them happens to be Dana White, president of the UFC, who runs around shouting things like "It's the safest sport in the world, fact."

This isn't true. Fighters die. A fighter is almost certainly going to die in Dana White's UFC some day. No one's ready for it.

Casualties are inevitable in any violent form of fighting. The list of well-known boxing deaths is depressingly long, and for everyone who's died, there are many more victims. And for every one of those we know aboutâ€"Muhammad Ali, say, or Terry Norris, whose story is strikingly told here by Leigh Cowartâ€"there are many more whose stories we haven't heard or noticed.

Muay Thai and kickboxing know tragedy, too. Dennis Munson, a Roufusport athlete, had a March 28 fight in Milwaukee in which he reportedly looked unsettlingly lethargic and clouded in the third round. He was taken to Mt. Sinai hospital, where he passed away later that night. (Roufusport has started a memorial fund to help his family.)

And despite the soundbites you may have heard, people have died while competing in MMA. It started with fighters taking part in unsanctioned events; the first known and most highly publicized was Douglas Dedge in 1998. It has continued with fighters in sanctioned events including Tyrone Mimms, Michael Kirkham, and Sam Vasquez. Most recently, we lost Booto Guylian after a fight in Extreme Fighting Championship Africa.

Beyond that, and again despite the prevailing public relations spin, people who have competed for the Ultimate Fighting Championship during the past 20 years have most certainly been the victim of serious injuries. What other word would you use for Frank Shamrock knocking out Igor Zinoviev with a slam that also obliterated his collarbone and ended his career? How would you categorize Cal Warsham taking a knee against Zane Frasier that broke his ribs, collapsed a lung, and put him in a hospital for a week? How about Corey Hill and Anderson Silva shattering their legs?

And then there's the head trauma. It's downplayed a bit because he also endured a punishing kickboxing career, but Gary Goodridge, a participant in several early UFC events who later appeared in Pride Fighting Championships, is suffering from obvious, serious symptoms of dementia pugilistica. Current UFC lightweight contender T.J. Grant is dealing with persistent concussion symptoms, and has put a previously promised title shot on hold while he recovers. Fighters like Nick Denis, Mac Danzig and many more have chosen to retire from the sport due to concerns about how their body was reacting to blunt head trauma. There's plenty of unverified speculation about the altered speech patterns and behavior in many aging fighters; over time we'll discover how many of our worst fears are justified. If excellent pieces like this one by Matthew Stanmyre are representative, and we accept what common sense and basic observation make readily clear, these problems are not at all isolated.

Some of the danger involved in professional fighting is intrinsic to what it is. It's possible that even in a utopian world of perfect regulation and officiating, smart training, less dangerous weight-cutting procedures, and safe-as-possible rule sets and equipment, MMA would still cause deaths and grave injuries. This is something that everyone who is in any way involved with the sport is left to grapple with. There are still aspects of the risk that are very much in our control. If we pass on opportunities to make a barbaric sport less barbaric, it really isn't much better than human cockfighting.

If we want MMA to be a real sportâ€"and it doesn't seem like we always do, but that's a different conversationâ€"we need to impose limits. With respect to Enson Inoue and his interpretation of Yamato-damashii, no one has a right to say, "No one stops this no matter what." Fighting isn't a bad movie, no matter how much it sometimes seems like one. Fighters should be prepared for the fact that in the absolute worst case, participating in the sport could lead to death or grave injury, but we should take all possible precautions to protect them, evenâ€"especiallyâ€"when they don't want to be protected. The moment a fighter is in serious danger, the fight should stop. The moment the damage a fighter is sustaining loses any purpose other than satisfying the worst impulses of the worst element of the crowd, someone has to tell him he's done.

We don't need 10 extra minutes of Josh Rettinghouse or Dan Lauzon* outmatched, hobbling around on one leg. We gain nothing by watching Junior dos Santos take the worst beating Cain Velasquez can deal out. We lost nothing when Urijah Faber wasn't given a chance to see how many of Renan Barão's hardest shots he could take. What we do risk losing are the fighters who bring us so much joy, and a bit of our humanity.

It's absolutely unnecessary for these men and women to show how tough they are. We know how tough they are. No one who has the courage to fight, whether on a low-level regional card or in a UFC main event, has anything to prove to anyone. And everyone in the sport has a role to play in making sure that it works in a way consistent with this central truth.

Promoters need to stop treating fighters who are good at winning without walking through concussive assaults, like Ben Askren, as boring and expendable. Corners need to stop treating the idea of throwing in the towel as something that robs fans of the fight they paid for. Commissions need to train doctors and referees to be more aggressive about stepping in when a fighter has had enough, and to always err on the side of caution. And fans need to start judging fighters by their skill and talent, not by how much they're willing to suffer.

None of this is going to happen, though, because the sport is what it is. And so it's a matter of time before we see not just a catastrophic injury or death in a high-profile MMA organization like the UFC or Bellator, but one that could have been prevented. In some ways, the worst of it won't be the thing itself. It will be the knowledge that it didn't have to happen.

Josh Tucker sometimes writes words. He mostly enjoys watching humans fight professionally, but is pretty conflicted about it. He's on Twitter @HugeMantis.

Photo via Getty Images

No comments:

Post a Comment