“You could feel the tension coming up, up, up from everybody,â€Â Gad told me. If he applied too much pressure with the biopsy needle, one of Tutankhamun’s fragile bones could easily snap. “But I put my faith in God, and we did it.â€

Two-and-a-half hours later, 15 tiny bone samples from sites scattered across each of the king’s legs had been safely deposited into little plastic tubes.

When Gad was finished, Corthals asked for a close-up shot on the video link. The fragments looked charred, and not as clean as the samples that they had taken from the other mummies. Tutankhamun was not going to be an easy mummy to deal with.

To determine how the royal mummies were related, the team now moved on to amplifying fragments of mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down the maternal line, as well as DNA from the male-determining Y-chromosome, which goes from father to son. The main goal, however, was genetic fingerprinting, Gad’s speciality, on the DNA inherited from both parents.

Unfortunately, over the millennia, black resins and other materials used in the embalming process had crept into the mummies’ bones. The effects were particularly bad for Tutankhamun, whose embalmers had poured so many bucketfuls of unguents over his mummy that it was found stuck fast to the bottom of his coffin. These impurities clung tight to the king’s DNA, blocking chemical reactions and turning the samples inky black. It took six months to figure out how to remove the contaminants, and prepare the samples for analysis.

Finally, the team got its first result from the boy king: a snatch of Tutankhamun’s Y-chromosome. Today, Gad says he can’t remember the actual moment when they realized they had their results. The version laid down in his memory is the one that the team re-enacted later for the TV cameras: a close-up of colored peaks on a computer screen followed by smiles and cheers, and team members shaking white-gloved hands.

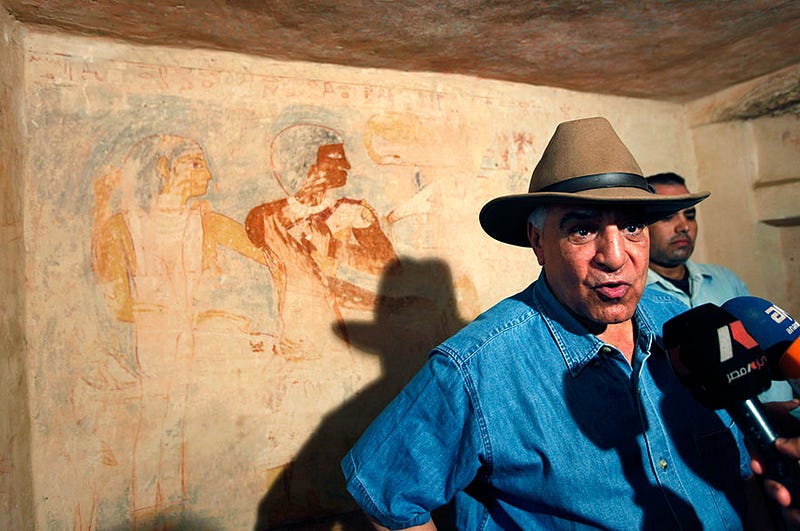

THE GRAND, COLUMNED HALLS of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo are usually dominated by stone giant statues and sarcophagi arranged to dramatic effect. But on February 17, 2010, all attention was focused on three neatly wrapped mummies. Behind them, four men sat in a row, their heads just visible over a forest of microphones carrying the logos of the world’s TV companies.

Gad and the team had exciting news for the waiting journalists. After amplifying DNA from every mummy they tested, they had constructed a five-generation family tree. The anonymous KV55 mummy, the team said, was actually Tutankhamun’s father, the revolutionary Akhenaten, while the foetuses were most likely his daughters. But the most jaw-dropping revelation was the secret that had felled the 18th Dynasty: Tutankhamun’s parents had been siblings.

Hawass ensured that the announcement was accompanied by a media blitz, including a research paper published in the esteemed Journal of the American Medical Association and a four-hour special on the Discovery Channel called King Tut Unwrapped. He later took to the pages of National Geographic to play up the ancient soap opera. The union between Akhenaten and his sister “planted the seed of their son’s early deathÂ,†he wrote. “Tutankhamun’s health was compromised from the moment he was conceived.â€

The team didn’t publish any information on the mummies’ racial or ethnic origins, saying that the data on the issue was incomplete. But that didn’t stop others from speculating. A Swiss genealogy company named IGENEA issued a press release based on a blurry screen-grab from the Discovery documentary. It claimed that the colored peaks on the computer screen proved that Tutankhamun belonged to an ancestral line, or haplogroup, called R1b1a2, that is rare in modern Egypt but common in western Europeans.

This immediately led to assertions by neo-Nazi groups that King Tutankhamun had been “white,†including YouTube videos with titles such as King Tutankhamun’s Aryan DNA Results, while others angrily condemned the entire claim as a racist hoax. It played, once again, into the long-running battle over the king’s racial origins. While some worried about a Jewish connection, the argument over whether the king was black or white has inflamed fanatics worldwide. Far-right groups have used blood group data to claim that the ancient Egyptians were in fact Nordic, while others have been desperate to define the pharaohs as black African. A 1970s show of Tutankhamun’s treasures triggered demonstrations arguing that his African heritage was being denied, while the blockbusting 2005 tour was hit by protests in Los Angeles, when demonstrators argued that the reconstruction of the king’s face built from CT scan data was not sufficiently “blackÂ.â€

For IGENEA, the whole affair was linked to a marketing exercise. It appears to have had no access to the data itself except a snapshot of a computer screen in a TV show, and yet the company now advertises a Tutankhamun DNA Project, which it describes as a search for the pharaoh’s “last living relatives.â€Â The company offers a variety of online DNA tests costing up to $1,500. The sweetener? If your profile matches that of the boy king, you get your money back. Gad refuses to even say whether IGENEA’s analysis of the DNA shown in the documentary is correct. “This is not,†he says, “how science should be conveyed.â€

Is there any culture in history that so many are so keen to lay claim to, whether for financial or political gain? “Owning†the pharaohs, it seems, means establishing a privileged place in history to being the founders of civilization. No matter that the ancient Egyptians were almost certainly an ethnically mixed group. They have become a mirror for whoever looks at them, focusing and reflecting the battles and prejudices of today.

Hawass and Gad’s triumphant announcement about Tutankhamun’s family triggered excited media coverage around the world. But what journalists didn’t report was that behind the scenes, the field of ancient DNA was locked in a bitter dispute. A few months later, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a short letter from Eske Willerslev and Eline Lorenzen at the Center for GeoGenetics in Copenhagen, Denmark, one of the world’s most respected ancient DNA labs. It tore Gad’s resultsâ€"and his reputationâ€"to shreds.

“In most, if not all, ancient Egyptian remains, DNA does not survive to a level that is currently retrievable,â€Â the pair wrote. “We question the reliability of the genetic data presented in this study and therefore the validity of the authors’ conclusions.†Roughly translated, it meant: “we don’t believe a word of it.â€

After the heady beginnings of the ancient DNA field in the 1980s and early 1990s, it didn’t take long for the fall. PCR turned out to be extremely susceptible to contamination, far more so than anyone had initially realized. Any trace of modern DNA in the environmentâ€"a speck of dust, a skin cell, a drop of sweatâ€"could dwarf any ancient DNA present and skew the results. In study after study, further analysis revealed that many of the genes that researchers had reported so proudly weren’t ancient at all. Woodward’s 80-million-year-old dinosaur DNA? It actually belonged to a modern human.

Researchers had to start again, with incredibly strict techniques and controls. Some experts refused to study human mummies at all, arguing that with the available techniques it would never be possible to know for certain that samples had not been contaminated by people who had previously handled the mummies, or by the researchers themselves. Instead, they looked at other speciesâ€"killer whales, penguins, cave bearsâ€"whose DNA is less likely to be floating around a lab.

Others scientists felt that the backlash had gone too far, however. They carried on working with human mummies, and publishing the DNA they amplified. The field divided into two campsâ€"the sceptics and the believersâ€"who published in different journals, attended different conferences, and refused to talk to each other. Researchers from the biggest labs, including Willerslev and Lorenzen, were in the sceptics’ camp. Many linked to the Egyptian Museum were believers.

Studies of Egyptian mummies were the most controversial of all, because DNA degrades quickly at high temperatures. Although it is possible to retrieve DNA from much older frozen specimens, such as mammoths, the sceptics argued that genetic material from Tutankhamun and his relatives couldn’t possibly have survived 3,000 years in the baking-hot deserts of Egypt. Far from uncovering the secrets of the pharaohs, Gad and his team had been fooled by cross-contamination with modern DNA.

Although Gad and his team wore gloves and masks when working on Tutankhamun, no previous archaeologists had done the sameâ€"from those unwrapping him in 1925 to those putting him through his CT scan some 80 years later. “You see TV people handling mummies with their bare hands, their sweat dripping on to the mummy,†Tom Gilbert, who heads two research groups at the Center for GeoGenetics, told me.“That’s a classic route of contamination.â€

Gad’s team had used other safeguards, including repeating some of their results in a second lab. But critics countered that the team didn’t publish its raw data, and didn’t sequence much of the DNA they amplified. Lorenzen, one of the authors of the letter that attacked Gad’s work, told me: “When working with samples that are so well-known, it is important to convince readers that you have the right data. I am not convinced.†She says she felt obliged to speak out after seeing the huge press coverage the results gained, lamenting that what she saw as flawed conclusions would now be taught in schoolÂ.

Other prominent scientists shared her concerns. The study “could do a much better job,â€Â complained Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, one of the founders of the ancient DNA field. Ian Barnes, an expert in the survival of ancient DNA at the University of London, said he would be “extremely cautious†about using the data. Gilbert, of GeoGenetics, was more blunt. “I’ve given up on the field a long time ago,â€Â he said. “It’s full of crap.â€

Gad and his colleagues had been under intense pressure “from Discovery and the forceful Hawass†to get results from incredibly difficult samples. Had they stared into a mix of messy data and contamination and imagined the family relationships they so desperately wanted to see? The team insisted their results were real. They couldn’t prove it, but they were convinced that the elaborate embalming techniques used on Egyptian royalty must have helped to preserve the mummy DNA.

“I don’t understand people’s harshness,†says Carsten Pusch, who joined the Egyptian Museum team soon after the samples were collected. He told me about detailing the months of painstaking experimentation it took to coax DNA from the mummies bones. “These people have never worked with royal mummies. This is pioneering work. I just wish everyone would give us more time.â€

Time was the one thing they turned out not to have.

No comments:

Post a Comment