by Dorothée Moisan  | photos by Jonathan Alpeyrie

When East Africa’s most feared terrorist group starts recruiting in Minneapolis, Somali-Americans spring into action to save their youthâ€"and the community’s reputation.

Photos by Jonathan Alpeyrie

Nairobi, Kenya, September 21, 2013â€"Gunmen from Al Shabaab, an Islamist group born in Somalia in 2006 and now linked to Al-Qaeda, attack the Westgate shopping mall and kill at least sixty-seven people. Confusion reigns in cyberspace, as some speak of a dozen of attackers. In reality, there are only four. A Twitter message claims that two of the assailants might have been raised in Minnesota, home to some 120,000 Somalis, the largest such community in the western world, ahead of cities like Toronto, London, Stockholm and Copenhagen. The rumor on Twitter is enough to magnetize the media. In a snap, cameras surround Cedar-Riverside, the Minneapolis neighborhood also known as "Little Mogadishu,†after the Somali capital. The tweet, however, was wrongâ€" one of the gunmen had spent several years in Norway but there is no confirmation about any attacker originating from the Twin Cities. The diaspora’s leaders condemn the violence, but not before a new harsh light has been turned on this community. Nobody can ignore the fact that since 2007, up to fifty young Somalis and Somali-Americans have left Minnesota for Mogadishu to join Al Shabaabâ€"whose names translates from Arabic as “The Youthâ€â€"and which was designated as a terrorist organization by the U.S. government in 2008.

Somali men pray inside a local mosque in Minneapolis.

Enhancing its marketing techniques, Al Shabaab circulated a YouTube video last August specifically targeting young Somalis in Minneapolisâ€"the city where the first known suicide bomber with American citizenship, the Somali-born Shirwa Ahmed, resided. On October 29, 2008, Ahmed drove a car loaded with explosives into a government compound in the north of Somalia, killing more than thirty. The YouTube video, “The Path to Paradise from the Twin Cities to the Land of Two Migrations,â€â€"which has been removedâ€"featured three youngsters from Minneapolis, two Somalis and an American convert to Islam, who have since died in East Africa, martyrs for the cause. On the forty-minute long video, the latter, Troy Kastigar, tries to attract supporters, laughing: “If you guys only knew how much fun we have over here, this is the real Disneyland! You need to come here and join us.â€

A Somali man walks under a bridge near the Cedar-Riverside area of Minneapolis, also known as "Little Mogadishu."

Mohamed Amin Ahmed uses cartoons to discourage Somali youth from joining Al-Shabaab.

Such videos shocked Mohamed Amin Ahmed, a thirty-eight-year-old Somali who arrived in the States twenty years ago with his parents and siblings. “I got frustrated,†says Ahmed. “I’ve got tons of nephews and they kept asking me: Is that our religion?†Ahmed, who fled the Somali civil war when he was eighteen, often wears a sorrowful look on his face, although in reality he is a happy husband and father-of-three living in a thick carpeted home in suburban Minneapolis.

In the nineties, Lutheran charities from Minnesota opened their arms to Somali refugees, two decades after they had welcomed the Hmong people from Southeast Asia. Far from Africa, Somalis discovered frosty weather, but also housing subsidies, and jobs in significant numbers, mostly in slaughterhouses and on assembly lines. After opening his own grocery in Minneapolis’ suburbs, Ahmed sold it and became the manager of a gas station, with the hope of one day achieving his American dream: to build a family-owned snack food factory.

“It takes an idea to kill an idea,†he loves to say. “And I’m full of ideas.†To deter children from martyrdom and provide an alternative to Al Shabaab’s propaganda, Ahmed created his own website, averagemohamed.com, where he posts short animated videos in English and Somali, explaining that suicide bombing is clearly against Islam.

One of Ahmed's animation videos explaining suicide bombing is not an acceptable part of  Islam.

Abdirizak Bihi, director of the Somali Education and Social Advocacy Center, based in Minneapolis, welcomes the initiative. “We reached a momentum,†he says. “But we need to redouble our work to make sure that people know Al Shabaab for what it is. We have to continue our awareness program and find resources. Above all, we need to eliminate the vulnerability of these young people by fighting poverty and unemployment, because Al Shabaab takes advantage of them.â€

Abdirizak Bihi, one of the Somali leaders in Cedar-Riverside,is involved in most of the community's affairs and its relationship with the U.S. authorities. His nephew was killed in battle in Somalia while fighting for Al Shabaab.

Bihi’s own life has been rocked by this radicalization. His nephew, Burhan Hassan, who landed in the United States at the age of four, was one of the young Minnesota residents who became taken with Al Shabaab.

It wasn’t until after Burhan had left that the family noticed warning signs. Bihi describes subtle changes noticed in his nephew and the other young men who left for Somalia: “We all found out that [in] the last three to six months, they all had changed. Every mother reported that they were not eating the food; they would be lying in their bed [staring at] the ceiling for hours. They had changed their appearances; they had cut off from their friends. They had stopped playing or watching their favorites games: hockey, basketball or football… They had completely shut down.â€

A group of Somali elders gathers at a public form in Minneapolis.

Hassan returned to Somalia in November 2008 and joined Al Shabaab, along with five other Somalis from the Twin Cities. As soon as the family realized that Burhan had flown back to Somalia, they phoned some relatives in Kenya, where the teenager was supposed to connect flights. "We missed him by only ten minutes at Nairobi’s airport," says Bihi.

Eight months later, Burhan called his mother and told her he wanted to go back home. He never did. When Al Shabaab fighters found out he wanted to quit and return to his family in Minneapolis, they killed him with a bullet in the head.

* * *

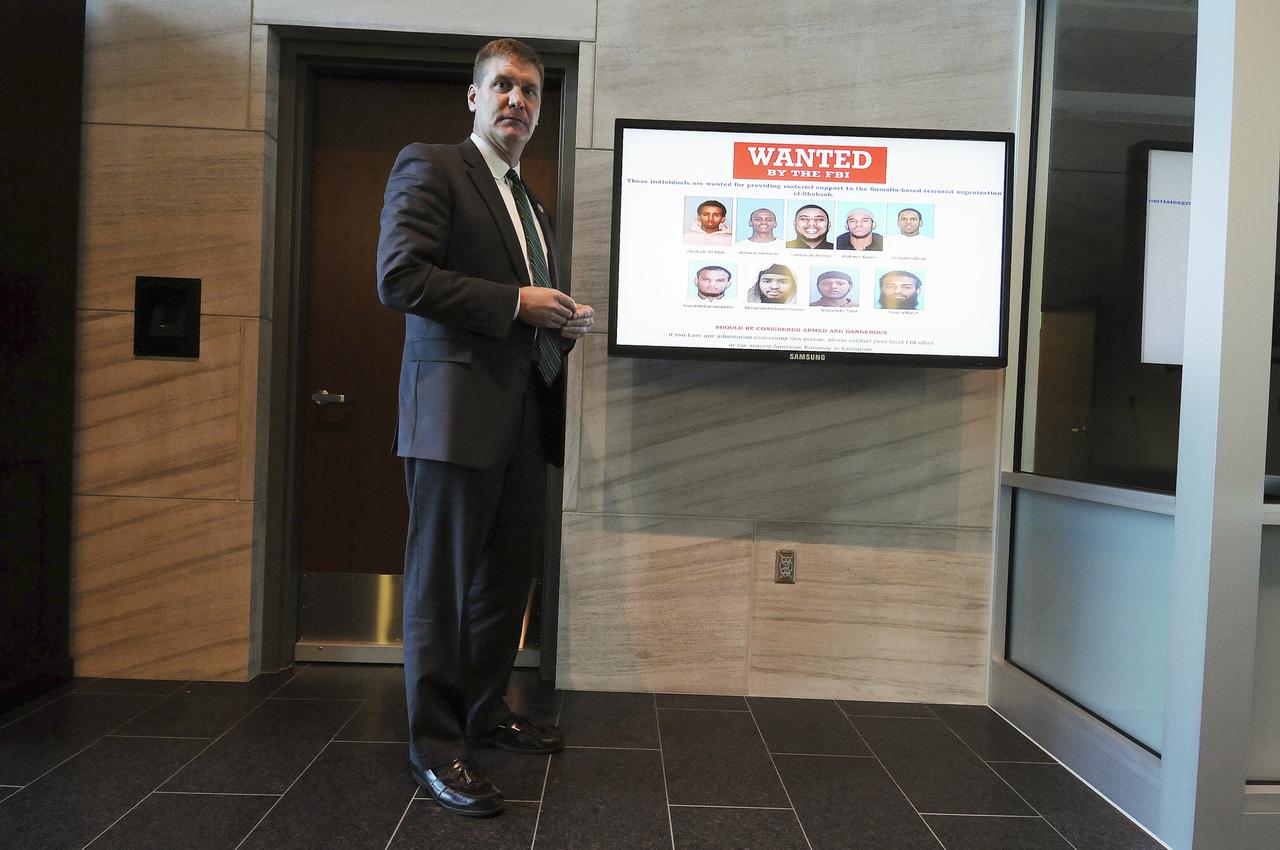

Kyle Loven, an FBI agent, is deeply involved within the Somali community, trying to stop young Somali men from joining gangs or Al Shabaab.

For the past six years, the jihadist threat has been the FBI’s top priority in Minnesota, with an ongoing investigation dubbed “Operation Rhino.†“The FBI,†explains Kyle Loven, Chief Division Counsel for the Bureau in Minneapolis, “became aware of the radicalization problem in the fall of 2007 when we were approached by people within the Somali community with respect of the disappearance of young men from the Twin Cities area. We believe the number to be somewhere between twenty and forty individuals.â€

A number of factors seem to have caused this exile, most linked to a general disaffection with American society. “[It’s] difficult to be proud of who you are when you watch the way Islam is treated on the news,†says Shirwa Hersi, twenty-seven, a Somali-born U.S. Marine who writes poems about this intractable challenge.

"Terrorism is Not a Religion," a poem by Shirwa Hersi, a Somali-born U.S. marine who writes about the challenges facing his community.

For many, lack of employment, the absence of a paternal authority figureâ€"two-thirds of the Somali homes in Minnesota would be single mother householdsâ€"and the general feeling of isolation seem to have played a role. Others saw the fight in Somalia as a religious duty, or calling to protect their homeland. As Imam Hassan Mohamud of Minnesota’s Da’wah Institute, and one of the community’s religious leaders, explains: “Before, in 2006, Al Shabaab was part of Islamic courts, and not only that, but there was an invasion by Ethiopian forces and Al Shabaab played an important role to free the country of that invasion… At that time, they were accepted.†After turning to terrorism and suicide bombings, “now they are against the Somali people itself.â€

The Da'wah Islamic Center in Minneapolis.

While some, like Bihi, accuse certain Minnesotan mosques of actively recruiting young jihadists on behalf of Al Shabaab, Hassan Mohamud swears to Allah that “no imam, even in the past, supported our young people in America to join any destructive group.†In fact, last September he flew to Mogadishu with other scholars and issued an Islamic fatwa condemning Al Shabaab. While some connections between Minnesota Somalis and Al Shabaab have been identifiedâ€"in 2012, the janitor of the Abubakar As-Saddique Islamic Center of Minneapolis was sentenced to twenty years in prison for aiding the terrorist groupâ€"the FBI has found no evidence of a genuine link between the mosques’ leadership and Al-Shabaab.

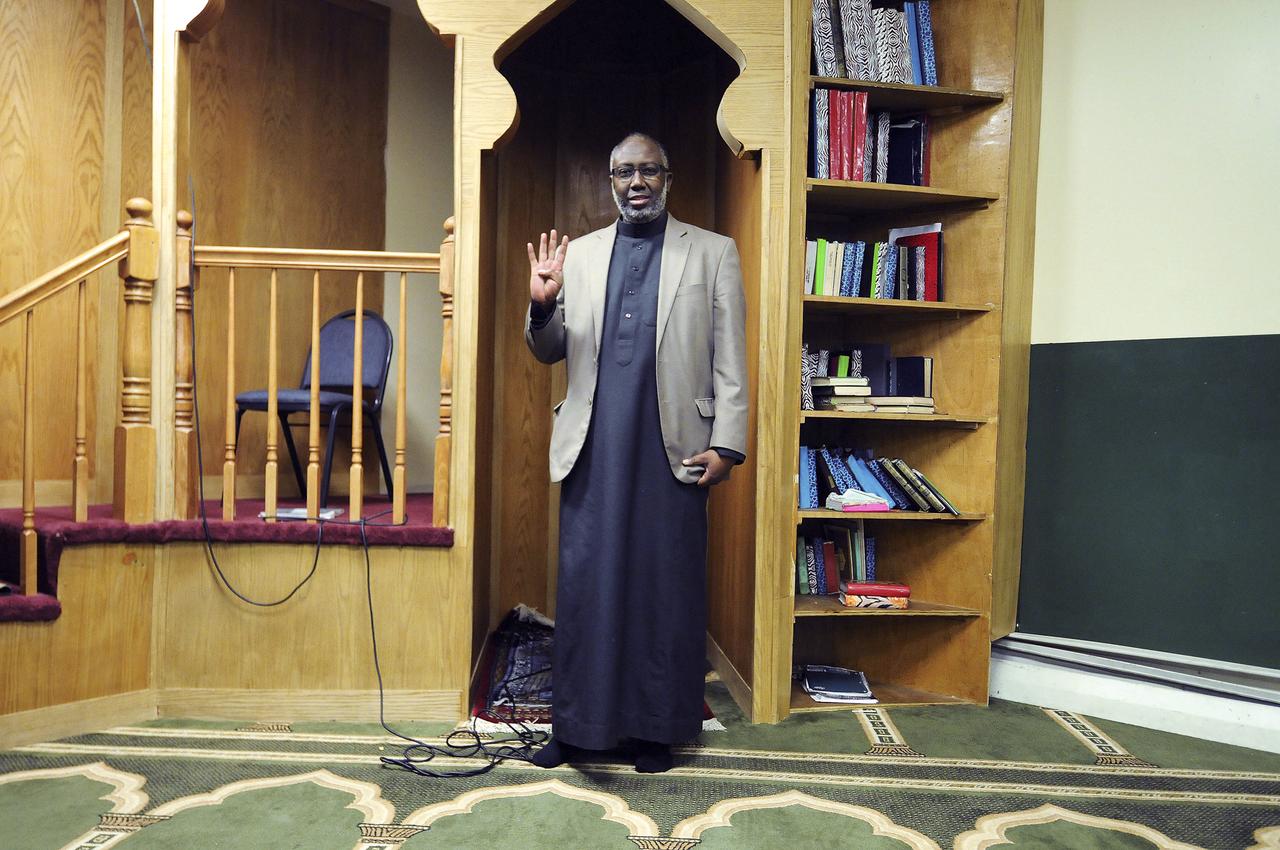

The imam Hassan Mohamud of the Da'wah Islamic center inside the mosque.

Bob Fletcher, a retired sheriff in Minneapolis, has been heavily involved in integrating the Somali community with the U.S. way of life.

Many would like to portray the Somali community in Minnesota as a haven for extremists. But time spent in the Twin Cities meeting with the diaspora in Somali mosques, malls, schools, businesses, and hookah bars tells a different story. For more than twenty years now, Somali refugees have worked hard for a slice of the American dream and Minnesota has been able to integrate these outsiders much more effectively than cities in Europe. “We still don’t do good enough,†acknowledges former Ramsey County Sheriff Bob Fletcher, who now runs the Center for Somalia History Studies, although he stresses that in other countries like Sweden, home to 44,000 Somalis, the unemployment rate among them is as high as fifty-five percent.

Somali youth socialize at a hookah bar in the subburbs of Minneapolis.

A group of Somali elders gather to listen to City Councilman Abdi Warsame.

“Certainly, we had some concerns with what happened in Kenya at the Westgate Mall but we are working through them and the best way is to open a discussion with the Somali community itself,†says Hennepin County Sheriff Rich Stanek. “The vast majority of the Somalis living here are law-abiding and good citizens,†he adds. Amongst them is Abdi Warsame, who in 2012 became the first Somali-American elected to the Minneapolis City Council, making him the most senior official of Somali descent in the United States. In late November, Warsame was shaking the hands of elders in Cedar-Riverside. “Today,†the City councilor said, “there are more Somalis serving in the U.S. Army, being policemen, civil servants or running businesses than terrorists. Unfortunately, that’s a story that’s not told.â€

A Somali woman near the Cedar-Riverside projects.

* * *

Born in France in 1975, Dorothée Moisan started to work for AFP, the French news agency, in 2000. She worked in Washington DC, Brussels and Paris. She published two investigative books, the first in 2011 about the former French president Nicolas Sarkozy and the second one last October about the hostages’ business. As a freelancer, her work has appeared in AftenPosten, Libération, ELLE and Radio France.

Born in Paris in 1979, Jonathan Alpeyrie moved to the United States in 1993. He has shot photographs for local Chicago newspapers, in the South Caucasus, Congo, the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. His work has appeared in The Sunday Times, Le Figaro magazine, ELLE, American Photo, Glamour, Aftenposten, Le Monde and BBC.

No comments:

Post a Comment