A YEAR OR SO before Patrick’s operation, a psychologist asked him if he would take a pill to make his BIID go away, should such a treatment exist. It took a moment for him to reflect and answer: maybe when he had been a lot younger, but not anymore. “This has become the core of who and what I am,†he said.

This is who I am. Everyone with BIID that I have interviewed or heard about uses some variation on those words to describe their condition. When they envision themselves whole and complete, that image does not include parts of their limbs. “It seems like my body stops mid-thigh of my right leg,†Furth told the makers of a 2000 BBC documentary, Complete Obsession.

“The rest is not me.â€

In the same film, the Scottish surgeon Robert Smith tells an interviewer: “I have become convinced over the years that there is a small group of patients who genuinely feel that their body is incomplete with their normal complement of four limbs.â€

It’s difficult for most of us to relate to a notion like this. Your sense of self, like mine, is probably tied to a body that has its entire complement of limbs. I can’t bear the thought of someone taking a scalpel to my thigh. It’s my thigh. I take that sense of ownership for granted. This isn’t the case for BIID sufferers, and it wasn’t the case for David. When I asked him to describe how his leg felt, he said, “It feels like my soul doesn’t extend into it.â€

Neuroscience has shown us over the past decade or so that this sense of ownership over our body parts is strangely malleable, even among normal healthy people.

In 1998, cognitive scientists at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh performed a deceptively simple experiment. They sat subjects down at a table with their left hands resting on a table. A screen prevented the subjects from seeing their hands: instead, a rubber hand was placed in front of the screen.

The researchers then used two small paint brushes to stroke both the real hand and the rubber hand at the same time. When questioned later, the subjects said that they eventually felt the brush not on their real hand, but on the rubber hand. More significantly, many said they felt as if the rubber hand was their own.

The rubber-hand illusion illustrates how the way we experience our body parts is a dynamic process, one that involves constant integration of various senses.Visual and tactile information, along with sensations from joints, tendons and muscles, gives us a sense of ownership of our bodies.This feeling is a crucial component of our sense of self: it’s about my body, my thoughts, my actions. It’s only when the process that creates this sense of ownership goes awry, for example when the brain receives conflicting sense information â€" as in the rubber-hand illusion â€" that we notice something is amiss.

And if we can feel as if we own something as inanimate as a rubber hand, can we own something that doesn’t exist? Seemingly, yes. Patients who have lost a limb can sometimes sense its presence, often immediately after surgery and at times even years after the amputation. In 1871, an American physician named Silas Weir Mitchell coined the phrase “phantom limb†for such a sensation. Some patients can even feel pain in their phantom limbs. By the early 1990s, it was established that phantom limbs were an artifact of body representation in the brain gone wrong.

The idea that our brain creates maps or representations of the body emerged in the 1930s, when Wilder Penfield probed the brains of conscious patients who were undergoing neurosurgery for severe epilepsy. He found that each part of the body’s outer surface has its counterpart on the surface of the cortex: the more sensitive the body partâ€"say, hands and fingers, or the faceâ€"the larger the brain area devoted to it. As it turns out, the brain maps far more than just the body’s outer surface. According to neuroscientists, the brain creates maps for everything we perceive, from our bodies (both the external surface and the interior tissues) to attributes of the external world. These maps compose the objects of consciousness.

The presence of such maps can explain phantom limbs. Though patients have lost a limb, the cortical maps sometimes remainâ€"intact, fragmented, or modifiedâ€"and they can lead to the perception of a limb, with its potential to feel pain. Even people born without limbs can experience phantom arms or legs. In 2000, Brugger wrote about a 44-year-old highly-educated woman, born without forearms and legs, who nonetheless had experienced them as phantom limbs for as long as she could remember. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation, Brugger’s team verified her subjective experience of phantom limbs and showed that body parts that were absent from birth could still be represented in sensory and motor cortices.

“These phantoms of congenitally absent limbs are animation without incarnation,†Brugger told me. “Nothing had ever turned into flesh and bones.†The brain had the maps for the missing body parts, even though the actual limbs had failed to develop.

When confronted with BIID, Brugger saw parallels to what the 44-year-old woman experienced. “There must be the converse, which is an incarnation without animation,†he said. “And this is BIID.†The body had developed fully, but somehow its representation in the brain was incomplete. The maps for a part of a limb or limbs were compromised.

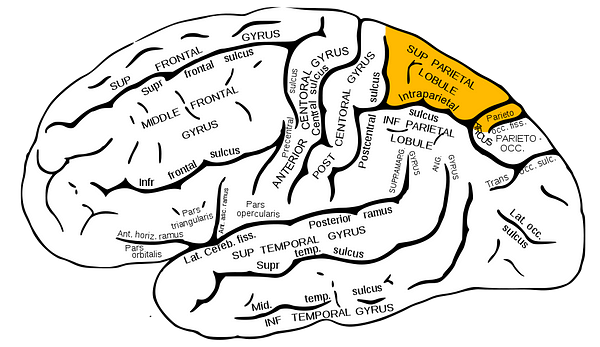

Recent studies have borne out this idea. Neuroscientists are particularly interested in the right superior parietal lobule (SPL), a brain region thought to be vital to the construction of body maps. Brugger has found that this area is thinner in those with BIID, and others have shown that it may be functioning differently in those with the condition. In 2008, Paul McGeoch and V.S. Ramachandran of the University of California, San Diego, mapped the activity in the brains of four BIID patients. The researchers tapped the feet of the control subjects and watched the SPL light up. But the BIID patients were different: the right SPL showed reduced activity when the disowned foot was tapped, only lighting up normally when the tap was on the other foot.

“What we argue is that in these people something has gone wrong in the development, either congenitally or in the early development, of this part of the brain,†McGeoch told me. “This limb is not adequately represented. They find themselves in a state of conflict, a state of mismatch that they can see and feel.â€

There are almost certainly other brain regions involved. Last year, scientists reviewed a number of “body-ownership†experiments, including the rubber hand illusion, and identified a network of brain regions that integrates sensory data related to maps of our body, its immediate surroundings and the movement of our body parts. These regions, they suggest, are responsible for what they call the “body-matrixâ€â€"a sense of our physical body and the immediate space around it. The network maintains the integrity of the body-matrix, and reacts to anything that threatens it.

Intriguingly, the physical differences in the brains of BIID patients that Brugger identified include changes in nearly all the parts of this network. Could BIID result from alterations to this body-matrix network? Brugger’s team thinks so.

It’s crucial to emphasize that these findings are correlationsâ€"they don’t address causality. Could a lifetime of thinking about amputating a leg lead to these brain changes? Or were these brain differences driving the desire? These studies cannot yet answer such questions.

Then there is the issue of how body states and body-matrix networks translate into a sense of self. And, for BIID patients, how a skewed body map leads to the desire for amputation.

“‘Owning’ your body, its sensations, and its various parts is fundamental to the feeling of being someone,†the philosopher Thomas Metzinger has written. He argues that our brain creates a phenomenal self-model (PSM), and the content of the PSM is our ego, our identity as subjectively experienced. If something is in the PSM, it belongs to me. If it’s not, then it’s not me. The rubber hand experiment works because it modifies the PSM: the brain replaces our real hand with the rubber hand, which is now embedded in the self-model. And since anything in the PSM has the subjective property of mineness, we feel as if the rubber hand belongs to us. In BIID, it’s likely that a limb or some other body part is misrepresented or underrepresented in the PSM. Lacking the property of mineness, it is disowned.

Therein lies a clue to why someone with BIID might want to amputate a limb that doesn’t feel like it belongs. My selfâ€"as defined by the content of the PSMâ€"is not just my subjective identity; it is also the basis for the boundary between what’s mine and everything else.

“It’s a tool and a weapon,†said Metzinger, when we spoke on the telephone. “It’s something that evolved to constantly preserve and sustain and defend the integrity of the overall organism, and that includes drawing a line between me and not-me, on very many different functional levels. If there is a misrepresentation in the brain that tells you this is not your limb, it follows that phenomenologically this will be a permanently alarming situation.â€

The debate rages on over whether amputation is ethical. In the meantime, BIID sufferers often take treatment into their own hands.

No comments:

Post a Comment