Undisputed Truth and the ever-changing Mike Tyson narrative

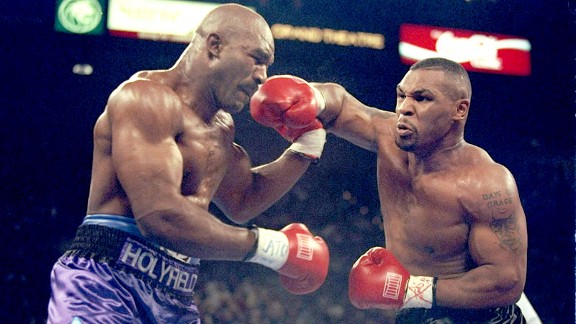

By Jay Caspian Kang onA quarter-century after he knocked out Trevor Berbick to win the heavyweight championship of the world, Mike Tyson has once again become an industry. All the other Tysons â€" the shy, gap-toothed prodigy who lisped about Harry Greb and Jack Dempsey; Kid Dynamite, the unbeatable force in black boots and black trunks; the undersize maniac who bit off a chunk of Evander Holyfield's ear; the convicted rapist in the denim shirt; the devout Muslim turned ranting, overweight lunatic; the sad mess of a fighter who quit on the stool against Kevin McBride; the tiger-owning, wailing bro from The Hangover â€" have all bled, slowly, inevitably, into something resembling a feeling. Mike Tyson, like all great, flawed, fictive characters in American history, makes you feel some kind of way, and throughout his life other men have profited wildly on that drawn emotion, whether awe, fear, disgust, or pity.

Since the 2008 release of Tyson, a tell-all James Toback documentary shot just days after Tyson left the Wonderland Treatment Center in Los Angeles, the ownership of the Mike Tyson industry has shifted, thankfully, finally, back to Mike Tyson. He is in the memoir trade now. In the past five years, Tyson has given dozens of candid interviews; shot a few television shows, including an Animal Planet series about his pigeons; taken his one-man show, Undisputed, on a national tour; and published a 580-page memoir titled Undisputed Truth. He has played himself in The Hangover and How I Met Your Mother and even found a role as Reggie Rhodes, a sympathetic murderer on Law & Order: SVU. Something strangely liberating happens to a man when he tells his life story over and over again. Circumstance overwhelms the innate and before too long, the man, who in this case is all of 47 years old, devolves into an abstracted, episodic run of small, meaningful scenes. Given enough time, all things â€" the loss to Buster Douglas, the rape conviction, the bankruptcy, the various addictions â€" can be explained away. If the historical Mike Tyson is a conflicted emotion, this new Mike Tyson has come to untangle the knot and trace each thread back to its horrific yet logical source.

If you're a boxing fan, you already know the structure of the Tyson story. He was born at Cumberland Hospital in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn and spent his young childhood years in Bedford-Stuyvesant. His father was a pimp named Jimmy "Curlee" Kirkpatrick Jr. Tyson's mother ultimately lost her job as a prison warden and the family had to move to Brownsville, where a young Tyson quickly fell into a life of crime. The mythic moment in which young Mike Tyson learned he could fight came after Tyson and his crew had broken into a house in Crown Heights and found $2,200 in cash. Tyson got cut in for $600 and used the money to buy some pigeons, which he stashed in an abandoned building back in Brownsville. A neighborhood bully named Gary Flowers heard about Tyson's windfall and tried to rob him. When Tyson went to confront him, Flowers, who had a pigeon stashed under his coat, ripped off the bird's head and smeared its blood on Tyson's face. When he has told this pigeon story in the past, Tyson has described the rage that overtook him and how he realized that his destiny would be a violent one. In Undisputed Truth, his explanation changes.

I had always been too scared to fight anyone before. But there used to be an older guy in the neighborhood named Wise, who had been a Police Athletic League boxer. He used to smoke weed with us, and when he'd get high, he would start shadowboxing. I would watch him and he would say, "Come on, let's go," but I would never even slap box with him. But I remembered his style.

So I decided, "Fuck it." My friends were shocked. I didn't know what I was doing, but I threw some wild punches and one connected and Gary went down. Wise would skip while he was shadowboxing, so after I dropped Gary, my stupid ass started skipping.

It's a small change, but one that radiates to nearly every page of Undisputed Truth. Throughout the narrative, Tyson tells you about all his influences â€" the stick-up kids in Brownsville, the juvenile correctional officers, the early trainers, the former great fighters he read about in Cus D'Amato's library up in Catskill, the crooked managers, the promoters, the imams, and the never-ending string of women out for his money. A less sympathetic reader might conclude, perhaps rightly, that the main lesson of Undisputed is that Mike Tyson believes that nothing Mike Tyson did was entirely Mike Tyson's fault. And if Mike Tyson had a traditional life, open to traditional moralizing and staid standards of accountability, perhaps Undisputed would read a little bit differently. But the reason why Mike Tyson has been able to hawk his story for so long and with such great success is because it falls so far outside the comprehension of anyone who did not grow up in an impoverished neighborhood during the dawn of the crack epidemic and then, by the age of 20, turn himself into the heavyweight champion of the world. Nobody has ever lived Mike Tyson's life, which is why it remains completely impervious to conflation.

By the age of 12, Tyson had fallen deep into substance abuse and had half of Brownsville looking for him. He was sent upstate to the Tryon School for Boys, a correctional facility for juvenile offenders. He quickly washed out of Tryon and ended up at a lockdown facility called Elmwood. There, Tyson met Bobby Stewart, a counselor who, in his free time, taught some of the boys how to box. Stewart immediately saw Tyson's potential and drove him down to Catskill, New York, to meet the legendary trainer Cus D'Amato. After a short sparring session, D'Amato had seen enough. He famously told Stewart, "That's the heavyweight champion of the world."

Tyson was 13 years old. He had never seen roses before his visit to Catskill and asked D'Amato if he could take some back to Tryon with him. D'Amato obliged and gave his new fighter a copy of a boxing encyclopedia. Back home at Tryon, Tyson read about great fighters like Benny Leonard and Harry Greb and Jack Johnson. On the weekends, he'd go back to Catskill to train with D'Amato, who broke down the psyche of his young pupil and built him back up with a series of mantras and affirmations that taught Tyson to detach his emotions from his actions, to subdue his fear and his anger and to act in a violent, intentional way through his body's own intuition. By the age of 14, Tyson had become fully immersed in both the past and the present of boxing. He stayed up all night watching fight films in D'Amato's screening room and read about the debaucherous lives of his old boxing heroes. He quickly shot through the young amateur ranks, won the Junior Olympics, and became a hot prospect in the heavyweight division. When he was 16, Tyson's mother fell ill with terminal cancer. He returned to Brownsville to accompany her during her last days.

This past March, I went to go see Tyson's one-man show at the Pantages Theater in Hollywood, and while I enjoyed the idea of the show, I could not help but feel the disconnect between this Tyson, who was selling himself as a decent, miraculous guy, and the Tyson I had seen in the 2008 Toback documentary. I do not claim to know which Tyson is more "real" or even if the two need to be distinguished from one another, but of all the guts Tyson spilled on the stage that night, one scene in particular stuck with me. He talked about his mother's funeral and how pathetic it had been and how, when he finally made some money, he went back to her burial plot and put up a massive headstone so that everyone would know that she had given birth to the greatest fighter of all time. A photo of the new headstone was projected up on the screen and the approximately 3,000 tough guys in the audience choked back their tears. It was one of those rare moments that can only be translated through the theater, where the man standing before you, in the flesh, has delivered a line that you know must devastate him every time he says it onstage, six days a week and twice on Sundays.

In Undisputed Truth, Tyson reveals what he said at his mother's grave site after her funeral. "Mom, I promise I'm going to be a good guy. I'm going to be the best fighter ever and everyone is going to know my name. When they think of Tyson, they're not going to think of Tyson Foods or Cicely Tyson, they're going to think of Mike Tyson."

What do you say to that?

In every scene with Tyson's mother, the reader can feel him struggle on the page. He tries to explain away his mother's cruelty, which included prolonged beatings, her alcoholism, and her stints as a prostitute, while also blaming her indifference, her absence for his misspent youth. In an early passage, Tyson talks about what happened after the family were evicted from their home in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

She'd never take us to a homeless shelter, so we'd just move into another abandoned building. It was so traumatic, but what could you do? This is what I hate about myself, what I learned from my mother â€" there was nothing you wouldn't do to survive.

I read Crime and Punishment as a disaffected teenager, and for years my interactions with my peers were shaped by Raskolnikov's lament: "Man grows used to everything, the scoundrel." Those seven words had more of an effect on me than Holden Caulfield's "phonies" or Kerouac's suffering, angelic, yet ultimately hypocritical seekers, and I'm certain that much of my outlook on humanity still comes from that horrible declaration. Reading Tyson's version â€" This is what I hate about myself, what I learned from my mother â€" there was nothing you wouldn't do to survive â€" uprooted me from the present and shot me straight back into all the dark, unctuous confusion of those adolescent years when we develop the conditional, ultimately hypocritical standards that animate our adult lives. This is what I hate about myself, what I learned from my mother â€" there was nothing you wouldn't do to survive.

The line is so powerful, so honest, and so awful that it nearly renders the rest of the book moot.

Fame came quickly for Tyson. This is the story we all know â€" the quick catapult up the boxing ranks, the string of knockouts, the cars, the tigers, the friendship with Anthony Michael Hall, the catastrophic marriage with Robin Givens, the Barbara Walters interview. Undisputed Truth gives us no new revelations about this period in Tyson's life, nothing that a devoted Tyson fan or a scholar of boxing has not already heard. The only difference between this particular telling of Tyson's life story (and I imagine there will be more to come) and what he revealed in his one-man show and in the Toback documentary is the heavy influence of the language of the therapist's office. Through his coauthor, Larry Sloman, who also wrote Private Parts with Howard Stern, Tyson describes and then attempts to rationalize pretty much everything that happened between his first title belt and his incarceration. If the Toback documentary did not exist, these extended looks into Tyson's mind might hold their own significance, but too often they read as if Tyson himself isn't even particularly interested in explaining why he lost to Buster Douglas in Japan or why he beat Mitch Green to a pulp.

Roughly 25 pages of Undisputed Truth are dedicated to Tyson's 1992 rape trial. As he did in his one-man show and he has done throughout his life, Tyson proclaims his innocence and reveals all the dirt his legal team found on his accuser, Desiree Washington, including a book deal she signed before the criminal trial, previous rape accusations that never saw a courtroom, and her family's plans for a civil suit seeking millions in damages. He dismisses the lawyer Don King hired for his defense as a "tax attorney" and speculates that King had given him the case as repayment for some unpaid loans. He brings up all the famous people who decried the verdict. Although Tyson and Sloman mount a vigorous defense, it should be noted that they preach to a choir made up of anyone who wants to read 580 pages on Mike Tyson, and that the evidence they present, while enough to prove that Tyson did not receive the fairest of trials, does not exonerate him.

When I saw him perform his one-man show in Los Angeles, Tyson, his hands at his side, his head bowed solemnly, stated, "I did not rape Desiree Washington." A nervous yet palpably enthusiastic energy ran through the audience, which did not seem to know whether to applaud. Finally, someone in the balcony broke the tension by yelling "I believe you, Mike!" The audience, suddenly liberated, cheered.

Women, in general, do not have an easy go of it in Undisputed Truth. Robin Givens and her mother are savaged as sociopathic gold diggers, and although one should certainly applaud a memoirist for being honest and forthright, the sheer volume of stories about casual sex with adoring fans, hangers-on, groupies, and prostitutes quickly turns boring and repetitive. At times, it almost seems as if Tyson and Sloman are trying to one-up Wilt Chamberlain's infamous 1991 autobiography, in which Chamberlain claimed to have slept with 20,000 women in his life.

If Undisputed Truth has a fatal flaw, it's this: Throughout the book, Tyson breaks scene to talk about how much he hates his past self. He claims to regret almost everything, save his relationship with Cus D'Amato, and then dredges up the reasons why he acted the way he did. This pattern extends to Tyson's views on women â€" he tells you about picking up five women a night and how roughly he would treat them and all the booze and drugs involved and then, in the middle of 580 pages that depict a man out of control, asks you to believe that his sexual activity never crossed over into any gray area. In the end, Tyson is asking you to judge his character not on a lifetime of misogyny or the angry outbursts in his memoir, but only by his claim that he did not rape Desiree Washington. I understand why he wants to clear his name, but I wonder if the one-sided testimony of a free, still-celebrated man about a case adjudicated 21 years ago can ever clear up anything.

The rest of the book is mostly sex and drugs and bad fights. Tyson reveals that he walked around with a brick of cocaine for personal use and spent nearly every day after his release from prison high on one drug or another. After his fighting days ended in 2005 with an ugly loss to a journeyman named Kevin McBride, Tyson slipped between treatment facilities and drug houses and celebrity cameos. He went bankrupt a few times and ended up with his current wife in a condo in Las Vegas, mourning the death of his daughter Exodus, who died in 2009 in a tragic accident involving a treadmill. Addiction memoirs, as a genre, always walk a thin line between self-indulgence and meaningful confession, and although Tyson's excesses almost demand their own super-genre, the shock wears off pretty quickly. I suppose the lack of a higher perspective betrays where Tyson still stands in his ongoing battle with drug and alcohol abuse. Undisputed Truth features a postscript to an epilogue that addresses Tyson's latest relapse, and although the writing there is forceful, it unravels any sense of closure the reader might have reached.

Maybe it's better this way. Tyson, after all, is only 47 years old. He's not dead yet, thank God.

On October 23 of this year, Frankie Leal, a 26-year-old Mexican fighter, died from brain injuries sustained during a knockout loss to Raul Hirales. Just 10 days later, Magomed Abdusalamov, a Russian heavyweight, was put into a medically induced coma after a brutal fight against Mike Perez that was broadcast on HBO. As of this printing, Abdusalamov, who had a portion of his skull removed to relieve pressure from brain swelling, has not regained consciousness. There is no rational way to explain Leal's death, and no perversion of morality or warrior metaphor will bring comfort to Abdusalamov's family. Boxing, once again, has no place in a civilized society.

It's always been this way, civility be damned. Boxing is the bastard child we want to stash away but cannot abandon because of just how much he reminds us of ourselves. I do not know why we feel the need to draw so much meaning out of the spectacle of two men punching one another in a ring or why we build weighty scaffolding around the bodies of fighters, but that impulse â€" to take a crude, wildly ambitious man, build him up, and then destroy him â€" runs through all American literary traditions. A book about boxing will always be shot through with ruin.

Beyond the unbelievable excesses and the magnitude of Mike Tyson's ongoing drama, our abiding interest in his story comes, at least in part, from the guilt and anger we feel over the wretched conditions that shaped his life. And here I am not only speaking to the bourgeois fan who looks at Tyson's ruin with voyeuristic glee or those who would read about Brownsville and immediately vacate all morality for paternalistic, and ultimately condescending, outrage for the hopelessness of the inner city. I am speaking, rather, to anyone who would turn any chapter of the Tyson saga into a larger symbol of all the brutality of our American lives. Boxing has provided a troubled, highly racialized, occasionally glorious metaphor for generations of writers in search of something raw, elemental, and, above all things, metaphoric, and I do not think it's any coincidence that the same things that were written about Tom Molineaux and brutality were written about Jack Johnson and brutality were written about Mike Tyson and brutality. The prospect of a man who literally beats his way out of poverty will always hold a broad appeal in a country committed to the mythos that naked ambition and hard work is all a man needs. The more horrific the ghetto, the more lavish the highs and the seedier the ruin, the better the story.

Maybe it's the boxing nerd in me, but as I read through Undisputed Truth, I felt drawn, again and again, to Tyson's discussions of all the old fighters he learned about in Cus D'Amato's fight library in Catskill. When D'Amato's strange education turned Tyson tabula rasa, a young Tyson built himself back up as the walking embodiment of every great champion. He was part Greb, part Henry Armstrong, part Jack Dempsey, part Jack Johnson, part Rocky Marciano, part Roberto Duran. Recently, Tyson talked about Duran in the 30 for 30 documentary No Más. In short, animated, and passionate segments, Tyson explained everything that was beautiful and terrible about Duran and how he took the crotch-grabbing, the meanness, the hellacious body shots, the bobbing and weaving, the aggression, the overall badness, and built himself into a heavyweight version of Manos de Piedra.

Tyson stole the show. I do not think anyone has ever loved boxing the way Mike Tyson loved boxing, and I am sure nobody has ever hated boxing the way Mike Tyson hated boxing. This makes him the perfect ambassador for a conflicted, awful, occasionally beautiful sport.

Boxing needs you, Mike. Get well.

No comments:

Post a Comment