By Hunter Oatman-Stanford

There’s plenty to hate about drivingâ€"traffic jams, car accidents, speeding ticketsâ€"not to mention the endless headache of finding a spot to park. So what if you discovered an invention that could wean us from our vehicles, combating suburban sprawl and making city streets less dangerous, congested, and polluted? Well, that device has been around for nearly 80 years: It’s called the parking meter.

Contrary to popular belief, the parking meter was originally designed to keep traffic moving and make more spaces available for shoppers, a measure often lauded by local businesses as much as the public who paid their hourly rates. Beginning with the first parking meter, installed in 1935 on the corner of First Street and Robinson Avenue in Oklahoma City, and spreading clear across the United States, the device was hailed as the great solution to our parking woes. Yet decades of poor meter implementation, inane off-street parking requirements, and technological stasis slowly turned our city streets into a driver’s nightmare.

“People who walk, bike, or take transit are bankrolling those who drive.â€

In the early 20th century, the United States rushed to embrace the independence and flexibility offered by motor vehicles, ignoring thousands of years of urban design in favor of the fast, cheap mobility automobiles provided. American towns were built to accommodate cars, rather than integrate them.

“The idea in force in American law at the start of the 20th century, that thoroughfares were for the movement of trafficâ€"with certain specific exceptions such as the loading and unloading of goods and passengersâ€"gave way fairly quickly to the idea that took root in the popular mind that parking of vehicles on the street was a right and not a privilege,†writes Kerry Segrave in “Parking Cars in America, 1910-1945.†In response, ill-conceived regulations helped cement the concept of free parking as a public good across America, fueling our dependence on automobiles.

Top: A forlorn driver in a Los Angeles parking lot, circa 1955. Image via the Los Angeles Public Library. Above: A  classic “Park-O-Meter†made by Magee-Hale in Bellaire, Ohio in 2011. Photo courtesy scottamus’s flickr stream.

Segrave notes that by 1920, city traffic jams were commonplace due to bountiful free parking without legal restrictions to encourage turnover. Street parking spaces were typically occupied by commuting workers, leading to snail-paced traffic and frequent double-parking as daytime drivers fought for the few spaces vacated during business hours. In many urban centers, more street space was filled with parked cars than moving ones. Unfortunately, most city leaders didn’t turn to mass transit as a solution to increased congestion, and actually used gridlock on downtown streets, frequently due to street parking, as an excuse to tear up efficient commuter tracks and inner-city rail systems.

The most visible instance of such degradation was the General Motors streetcar scandal: Beginning in the late 1930s, several automobile-related businesses, including GM, Firestone, and Standard Oil, created front companies to purchase and dismantle rail-based transit systems, especially inner city tramways, and replace them with less efficient bus lines. In 1949, the companies would be convicted of a conspiracy to monopolize transportation, but the damage was already done.

Left: In the 1930s, Parker Brothers’ earliest “Monopoly†sets already included the requisite space for free parking. Right: During the 1920s, an absence of restrictions meant that the majority of American city streets were devoted to free parking, rather than the flow of moving vehicles.

In fact, automobile congestion had been a problem since the late 1910s, so much so that several cities, including Los Angeles, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia, passed laws completely outlawing street parking in their central business districts. However, public protest and pressure from local businesses soon overturned such bans in favor of restricted time limits on downtown streets. Yet enforcement was still inadequate, as police departments typically used a poor system of patrolling streets on foot and marking tires with chalk to indicate payment.

Then, in July of 1935, a novel technological effort to improve parking turnover was initiated in Oklahoma City, where entrepreneurs Carl Magee and Gerald Hale designed the world’s first parking meter, ominously dubbed “The Black Maria.†Using a coin-operated timing system, their meters displayed a red flag once payment had expired, making parking laws much easier to enforce. As a trial, the Magee-Hale “Park-O-Meter†Company installed 200 machines along a 14-block stretch of downtown, divided into 20-foot spaces. They agreed to place meters on one side of the streets at no charge to the city with the understanding that their initial capital cost would be repaid by the five-cent hourly rate, after which the city would reap all parking fees.

On their first day of operation, motorists tentatively adopted the new meter technology, but by the end of the first week, shops fronting parking meters reported increased sales, prompting establishments on the opposite side of the street to beg the city for their own magical meters. The following year, a New Republic editorial praised the device’s effectiveness, calling it “the next great American gadget.â€

As the New Republic explained, the mechanism had “already spread to Texas, Florida and Michigan and seems likely to sweep the country.†In addition to benefitting city treasuries and increasing parking turnover, the article claimed few motorists opposed the device, and many “warmly approve it.†Though there was some backlash from drivers who accused municipalities of charging a new tax on roads, a publicly owned property, cities successfully defended meter fees in court as a way to fund parking regulation and enforcement.

Residents watch with excitement and trepidation as the first meters are inaugurated in Washington, DC, in 1938. Photo courtesy Roth Hall.

During the late 1930s, to serve the growing demand for parking meters, several new companies followed Magee-Hale’s lead, like M.H. Rhodes’ Mark-Time meters and the Duncan-Miller Company. In 1938, American City magazine reported that 85 municipal areas had installed new meters, and Segrave says, “those cities were practically unanimous in praising the machines and what they had done in solving their cities’ parking problems.â€

“Cities were practically unanimous in praising the machines and how they’d solved their parking problems.â€

Meanwhile, local governments began establishing off-street parking requirements for new buildings in a further attempt to eradicate traffic jams and force developers to accommodate private motor vehicles. A 1946 survey of 76 cities found that only 17 percent had parking requirements in their zoning ordinances, but only five years later, 71 percent had off-street requirements or were in the process of adopting them. Thus began the great American sprawl: Since most new construction was required by law to include a minimum number of parking spaces, gigantic parking lots and hulking city garages grew like tumors from city streets.

In his definitive book, “The High Cost of Free Parking,†Donald Shoup explains that minimum parking requirements “led planners and developers to think that parking is a problem only when there isn’t enough of it. But too much parking is also a problemâ€"it wastes money, degrades urban design, increases impervious surface area, and encourages overuse of cars.†Besides the fact that legally required lots are often more than half-empty, they result in a variety of negative impacts, from environmental runoff issues to inhospitable pedestrian zones. Instead of using the tools available to limit automobile use and encourage free-flowing street traffic, Shoup explains that planners traditionally did the opposite, requiring “enough off-street spaces to satisfy the peak demand for free parking.â€

Additionally, such ordinances falsely reduced the explicit cost of city driving, transferring the true expense of so-called “free†parking to every citizen in the vicinity, diffused into taxes, real estate, product, and service fees. In effect, this legislation created an environment where “nobody can opt out of paying for parking,†says Jeff Speck, renowned urban planner and author of the book, “Walkable Cities.â€

According to Speck, “people who walk, bike, or take transit are bankrolling those who drive. In so doing, they are making driving cheaper and thus more prevalent, which in turn undermines the quality of walking, biking, and taking transit.†Furthermore, our plethora of free parking resulted in a range of negative consequences still unaccounted for: “The social costs of not charging for curb parkingâ€"traffic congestion, air pollution, accidents, wasted time, and wasted fuelâ€"are enormous,†writes Shoup.

By 1950, as a concession to the automobile’s omnipresence, parking meters had spread to most urban centers in the United States. An article in The Rotarian claimed that “most motorists like the parking-meter idea, for they find curb parking spaces more easily in metered districts. Merchants say that this easier parking improves their business.†The story also highlighted the great return cities had seen from parking revenue, which was used to pay regulatory policemen or trendy new meter-maids and also to expand off-street parking. For the next fifty years, the U.S. used its parking meters in almost exactly the same way.

By the 1950s, parking regulations were much easier to enforce thanks to the nifty new meters. Photo courtesy Roth Hall.

Meanwhile, in Europe, where cities were predominately built without the car in mind, meters continued evolving to curb the negative impacts of private vehicles. “Although the parking meter was invented in the U.S.,†says Shoup, “most of the subsequent technological progress has been made in Europe, where the scarcity of parking creates a demand for more efficient and convenient metering.â€

European cities have been quicker to adopt modern payment methods, such as credit cards linked to mobile phone applications or license plate numbers. Furthermore, their planners recognize the power of parking to manipulate driving habits: A 2011 report called “Europe’s Parking U-Turn†by Michael Kodransky and Gabrielle Hermann states that “every car trip begins and ends in a parking space, so parking regulation is one of the best ways to regulate car use.â€

“Most motorists like the parking meter idea, for they find curb parking spaces more easily.â€

Today, parking covers more of urban America than any other single-use space, yet the vast majority of meters are outdated, coin-only devices, charging a flat-rate during operating hours across all zones. “From the user’s point of view, most American parking meters remain identical to the original 1935 model,†writes Shoup. “You put coins in the meter to buy a specific amount of time, and you risk getting a ticket if you don’t return before your time expires. The main change in 70 years is that few meters now take nickels. In real terms, however, the price of most curb parking hasn’t increased; adjusted for inflation, 5 cents in 1935 was worth 65 cents in 2004, less than the price of parking for an hour at many meters in 2004.†Once praised as the answer to our auto problems, the invention has languished on American sidewalks. (POM, Inc., the descendant of the Magee-Hale company, is still producing standard meter designs, albeit with digital LCD screens and credit card payment modules.)

Studies show that under-priced meters have created a false sense of scarcity for drivers, who instead spend more time and gas circling the block than if they parked off-street in a free garage and walked to their destination. “The goal, of course, is to price both on-street and off-street parking in a carefully strategized way that results in cars being where you want them, when you want them, and keeps a 15 percent vacancy along the curb as Shoup recommends,†says Speck. “The parking meter and the price of parking is a tremendously powerful tool that cities can use to see their downtowns thrive.â€

Shoup boils his recommendations down to three basic solutions to the parking disaster: Charge fair market prices for on-street parking, dedicate meter revenue toward public improvements on metered streets, and remove off-street parking requirements. “I think that more and more planners are beginning to realize that what they were saying as a routine thing was dangerous nonsense,†adds Shoup.

Ground zero for the U.S. parking revolution is San Francisco, one of the country’s most pedestrian-friendly cities. In 2011, the City of San Francisco instituted the groundbreaking SFpark program, outfitting certain neighborhoods with advanced meters and parking sensors whose rates can be programmed based on vehicle occupancy and turnover (Duncan Industries, originally called Duncan-Miller and one of the earliest meter manufacturers, is responsible for a portion of San Francisco’s new devices). Since the project’s debut, meter rates have been adjusted every six weeks to reach an optimal hourly charge that will keep between most meters occupied with a few always open for new vehicles. Recently, the San Francisco Examiner found the project to be an overall success, with parking rates and fines actually decreasing across the city even as spaces become more available.

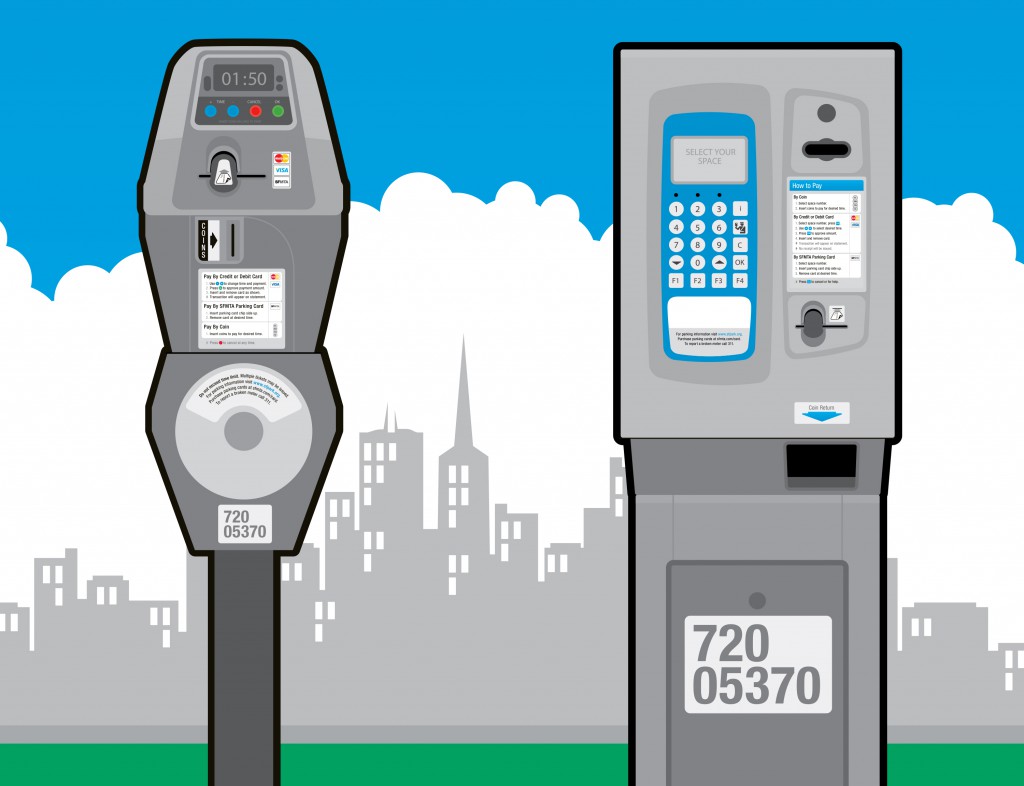

A rendering of the new individual and multi-space machines installed for the SFpark program.

Though San Francisco is not the norm, Donald Shoup is hopeful about the results of parking meter experiments in smaller cities like Ventura, California, which installed an updated meter system in 2010 to allow for credit-card payments and improved meter pricing. Ventura offers a stellar example of what Shoup calls a “parking benefit district,†or a neighborhood that institutes updated parking policies, and in return spends its parking revenue on neighborhood improvements. As a result of its meter upgrades, the city was able to pay for street improvements and provide free wi-fi across its central business district, not to mention hiring parking-enforcement officers whose presence has helped reduce crime rates up to 40 percent.

“Parking reform is such a terrific opportunity for improving city life,†says Speck. “It’s something quite small that can be done on a single block; it’s very incremental. All the data is there. You just need to open your eyes.â€

No comments:

Post a Comment